http://24corners.blogspot.com/ asked me:

Have you ever read any of Ellen's letters to Charlotte? I've only read Charlotte's to her. It would be nice to hear Ellen's voice, as it has been so nice to hear Mary's.

Have you ever read any of Ellen's letters to Charlotte? I've only read Charlotte's to her. It would be nice to hear Ellen's voice, as it has been so nice to hear Mary's.

I like this question and I am looking for an answer.

I found this information about a letter from Charlotte, it is not about the topic, but still interesting.

A letter by Charlotte Brontë found in a laundry room

Over 350 letters from Charlotte Brontë to Nussey were used in Gaskell's The Life of Charlotte Brontë he prevented at least one other publication from using them. Following Nussey's death in 1897, aged 80, her possessions and letters were dispersed at auction, and many of Brontë's letters to her eventually made their way through donation or purchase to the Brontë Parsonage Museum in Haworth in Yorkshire.

Catalogue of letters

http://www.ampltd.co.uk/collections

(This is interesting, doesn't have to do with the letters I am searching for.

http://www.spring.net/ )

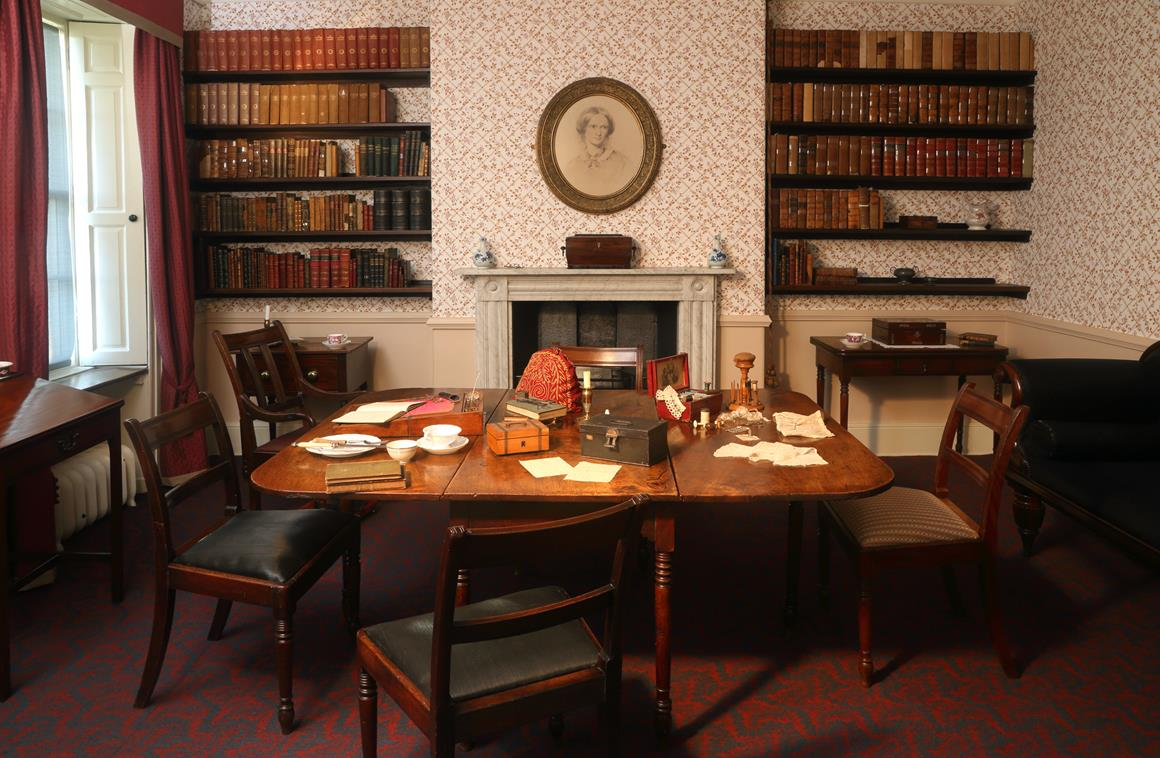

Ellen Nussey, visiting Haworth for the first time some twenty years earlier, also found the Parsonage scrupulously clean but considerably more austere. There were no curtains at the windows because, she said, of Patrick's fear of fire though internal wooden shutters more than adequately supplied their place.

'There was not much carpet any where except in the Sitting room, and on the centre of the study floor. The hall floor and stairs were done with sand stone, always beautifully clean as everything about the house was, the walls were not papered but coloured in a pretty dove-coloured tint, hair-seated chairs and mahogany tables, book-shelves in the Study but not many of these elsewhere. Scant and bare indeed many will say, yet it was not a scantness that made itself felt . . .'

In 1871, Ellen Nussey, a lifelong friend of the Brontës, wrote of her first impressions of the fifteen-year-old Emily in Reminiscences of Charlotte Brontë:

Emily Brontë had by this time acquired a lithesome, graceful figure. She was the tallest person in the house, except her father. Her hair, which was naturally as beautiful as Charlotte's, was in the same unbecoming tight curl and frizz, and there was the same want of complexion. She had very beautiful eyes – kind, kindling, liquid eyes; but she did not often look at you; she was too reserved. Their colour might be said to be dark grey, at other times dark blue, they varied so. She talked very little. She and Anne were like twins – inseparable companions, and in the very closest sympathy, which never had any interruption.

http://www.wuthering-heights.co.uk/emily.htm

Have you ever read any of Ellen's letters to Charlotte? I've only read Charlotte's to her. It would be nice to hear Ellen's voice, as it has been so nice to hear Mary's.

Have you ever read any of Ellen's letters to Charlotte? I've only read Charlotte's to her. It would be nice to hear Ellen's voice, as it has been so nice to hear Mary's.I like this question and I am looking for an answer.

I found this information about a letter from Charlotte, it is not about the topic, but still interesting.

A letter by Charlotte Brontë found in a laundry room

This book is about Ellens' letters, but now ....

are Ellen's letters on internet?

Over 350 letters from Charlotte Brontë to Nussey were used in Gaskell's The Life of Charlotte Brontë he prevented at least one other publication from using them. Following Nussey's death in 1897, aged 80, her possessions and letters were dispersed at auction, and many of Brontë's letters to her eventually made their way through donation or purchase to the Brontë Parsonage Museum in Haworth in Yorkshire.

Catalogue of letters

http://www.ampltd.co.uk/collections

(This is interesting, doesn't have to do with the letters I am searching for.

http://www.spring.net/ )

Ellen Nussey, visiting Haworth for the first time some twenty years earlier, also found the Parsonage scrupulously clean but considerably more austere. There were no curtains at the windows because, she said, of Patrick's fear of fire though internal wooden shutters more than adequately supplied their place.

'There was not much carpet any where except in the Sitting room, and on the centre of the study floor. The hall floor and stairs were done with sand stone, always beautifully clean as everything about the house was, the walls were not papered but coloured in a pretty dove-coloured tint, hair-seated chairs and mahogany tables, book-shelves in the Study but not many of these elsewhere. Scant and bare indeed many will say, yet it was not a scantness that made itself felt . . .'

In 1871, Ellen Nussey, a lifelong friend of the Brontës, wrote of her first impressions of the fifteen-year-old Emily in Reminiscences of Charlotte Brontë:

Emily Brontë had by this time acquired a lithesome, graceful figure. She was the tallest person in the house, except her father. Her hair, which was naturally as beautiful as Charlotte's, was in the same unbecoming tight curl and frizz, and there was the same want of complexion. She had very beautiful eyes – kind, kindling, liquid eyes; but she did not often look at you; she was too reserved. Their colour might be said to be dark grey, at other times dark blue, they varied so. She talked very little. She and Anne were like twins – inseparable companions, and in the very closest sympathy, which never had any interruption.

http://www.wuthering-heights.co.uk/emily.htm

CONCLUSION:

I only find letters from Charlotte to Ellen,

but no letters of Ellen to Charlotte

but no letters of Ellen to Charlotte

I read on an website that non of the letters of Ellen exists anymore.

When I go to this website again I am not allowed anymore.

What I did read was:

Presumably they were destroyed just as Nussey was asked by Brontë’s husband Arthur Bell, soon after their marriage, to destroy those she had received from Brontë because of their ‘passionate language’. She refused.

A surviving letter from Charlotte to Ellen dated 20 october 1854 shows her husband’s surveillance in action:

A surviving letter from Charlotte to Ellen dated 20 october 1854 shows her husband’s surveillance in action:

Arthur has just been glancing over this note . . . you must BURN it when read. Arthur says such letters as mine never ought to be kept, they are dangerous as Lucifer matches so be sure to follow the recommendation he has just given, ‘fire them’ or ‘there will be no more,’ such is his resolve . . . he is bending over the desk with his eyes full of concern. I am now desired to have done with it . . .

The writer of the book Letters tot Charlotte Caeia March keeps an weblog, she writes:

The next day I had a small an intimate reading in a friend’s home – a warm and friendly gathering in which I was asked: Why do you think that Ellen Nussey chose not to burn her letters? This I shall answer more fully in an Ezine article soon. Here I would comment that I am certain she kept them as an embodiment of the Charlotte whom she had loved so deeply and for all of her own life. Ellen did not die until she was over eighty, in the November of 1897. I think she would have read and reread Charlotte’s hand writing, imagining or even feeling Charlotte’s presence though the sight of the formed words and phrases and the shape of the signatures.

What I wonder is: Is this about the letters Charlotte wrote to Ellen, or also about the letters Ellen wrote to Charlotte.

Question: What happened to the letters Ellen Nussey sent to Charlotte Bronte?

We have quite a mystery here don't we!? I wonder if Arthur disposed of Ellen's letter's to Charlotte...but like you said, then how could there be a book about them if they were destroyed.

BeantwoordenVerwijderenIn Charlotte's and Anne's books, you can see that women who were good friends spoke much more affectionately to one another than they do today, this can be seen in Charlotte's letters to Ellen and even is some to other. Her friendships meant so much to her, especially during times of agony and loneliness.

I know that Arthur was appalled in the way that Charlotte and Ellen discussed and analyzed people's characters (just as women are want to do) and I believe that is the reason he wanted the letters destroyed, he was shocked by the openess of character assasination and dissection...I don't believe it was more than that.

It seems that searching for Ellen's letters will be an interesting hunt!

xo J~

I just came back from Amazon.com as I was looking up "Letters To Charlotte", and discovered that these are fictionalized letters from Ellen. There are three reader reviews which were interesting to read though.

BeantwoordenVerwijderenSomeone has to know what happened to those letters, so strange!

xo J~

Charlotte did not keep Ellen's letters. I believe she routinely burned others letters

BeantwoordenVerwijderenWhen CB sent Ellen the letter where Rev Bronte signed off as Flossy to read , CB said

" you are free to burn this after reading "

and CB's routine of burning of letters is why when Arthur said Ellen must burn Charlotte's letters,

Charlotte said " okay fine " lol

As far as I can tell the only, letter Charlotte kept was Southey 's

and you know what? I don't think Ellen's were that great anyway

I'd much rather have Mary Taylor's letters to CB lol