I am searching for more information about these letters.

In this letter Louise Heger describes how one morning in 1913 she heard men selling the newspaper Le Petit Blue shouting about the ‘love affair’ of Monsieur Heger. She and her brother Paul had just given the letters Charlotte wrote to Monsieur to the British Museum, after which they were published in The Times.

In this letter Louise Heger describes how one morning in 1913 she heard men selling the newspaper Le Petit Blue shouting about the ‘love affair’ of Monsieur Heger. She and her brother Paul had just given the letters Charlotte wrote to Monsieur to the British Museum, after which they were published in The Times.

Louise Heger was born in 1839, 3 years before Charlotte and Emily Brontë enrolled at the Pensionnat Heger. She studied under the Belgian Impressionist Alfred Stevens and painted in a studio at the bottom of the Pensionnat Heger garden. Louise was a successful landscape artist and exhibited a Coastal Landscape and a View of the River Ourthe at an 1893 exhibition inBrussels

She died in 1933 .thebrusselsbrontegroup.org/heger

Since the October excursion I have been greatly assisted by Renate Hurtmanns, who paid several more visits to Evere cemetery, as you can see from her report below, with the latest on this research. She has also helped me in transcribing letters written by Louise Heger, the daughter of Monsieur and Madame Heger. Some time ago I discovered that the Ghent Museum of Fine Arts has a large very interesting collection of letters written by her, including many she wrote to her parents, sisters and brother that give a valuable new insight into the family. In this letter Louise Heger describes how one morning in 1913 she heard men selling the newspaper Le Petit Blue shouting about the ‘love affair’ of Monsieur Heger. She and her brother Paul had just given the letters Charlotte wrote to Monsieur to the British Museum, after which they were published in The Times.

In this letter Louise Heger describes how one morning in 1913 she heard men selling the newspaper Le Petit Blue shouting about the ‘love affair’ of Monsieur Heger. She and her brother Paul had just given the letters Charlotte wrote to Monsieur to the British Museum, after which they were published in The Times.Louise Heger was born in 1839, 3 years before Charlotte and Emily Brontë enrolled at the Pensionnat Heger. She studied under the Belgian Impressionist Alfred Stevens and painted in a studio at the bottom of the Pensionnat Heger garden. Louise was a successful landscape artist and exhibited a Coastal Landscape and a View of the River Ourthe at an 1893 exhibition in

She died in 1933 .thebrusselsbrontegroup.org/heger

Exhibition and Lecture at Museum M, in Leuven

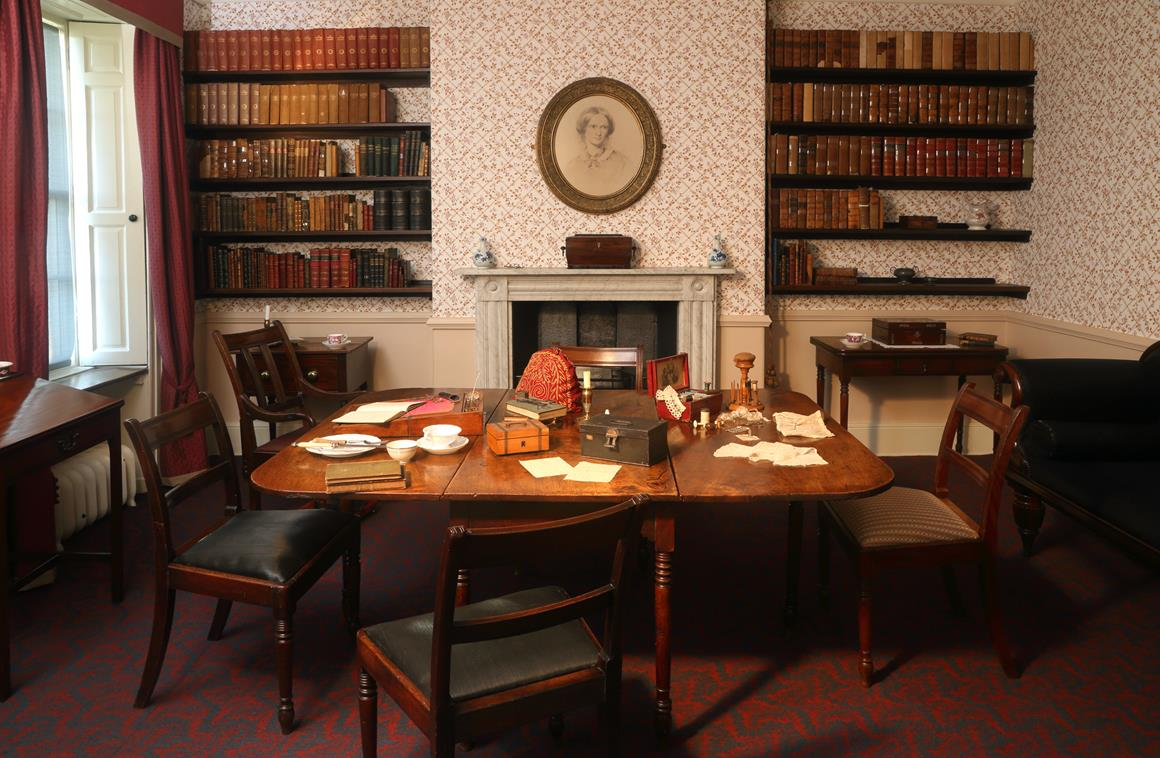

On October 27, 2011 several members of the Brussels Brontë Group went to Leuven to an exhibition of paintings and drawings by two Belgian women artists, Isala van Driest (1842-1916) and Louse Heger (1839-1933), and in the evening to a lecture by Professor Sue Lonoff of Harvard University on Louise Heger and Charlotte Brontë. The exhibition was called ‘Isala & Louise, Two Women Two Stories’. Remarkably their surnames were not part of the title, probably to stress the invisibility of women in the professions at the time, for its theme was how these two gifted women overcame prejudice and forged a way into what were conventionally regarded as male preserves – Isala van Driest as a medical doctor, and Louise Heger as an artist specializing in landscape painting and drawing.

Of crucial interest was the role Louise played many years later when her parents were long dead, namely what was to become of the letters Charlotte wrote to her teacher M Heger when she had left Brussels for the last time. Louise knew that at least some of them had been kept, having first been torn up and subsequently pieced together, perhaps by Mme. Heger. The actual facts are not really known. But Louise did know that her mother wanted them to be preserved and had therefore bequeathed them to her. Even during Mme Heger’s lifetime Charlotte Brontë had become a very famous author and Mme wanted to scotch any insinuation that her relationship with her husband had been anything other than a schoolgirl’s crush. So it was Louise who initiated the quest to preserve the four letters for posterity – on the one hand to exonerate her father altogether and on the other, as part of British literary heritage. She discussed the case with her brother Paul who knew nothing about the existence of the letters. They decided to consult an eminent English art-critic, Marion Spielmann, and at his suggestion donated the letters to the British Museum (they are now in the British Library) in 1913. Later on they were published in The London Times -- and caused a sensation.

In his writings on the subject Spielmann seems to play down Louise’s role in the preservation of the letters, possibly, as Sue Lonoff implied, because he had a tendency to disregard the female in any but a conventional role; on the other hand, Louise herself may have been too modest a person (we might say under-assertive) to claim her true position. More might come to light as research is done on the life and work of Marion Spielmann. brusselsbronte.blogspot.com/exhibition-and-lecture-at-museum-m-in.html

In his writings on the subject Spielmann seems to play down Louise’s role in the preservation of the letters, possibly, as Sue Lonoff implied, because he had a tendency to disregard the female in any but a conventional role; on the other hand, Louise herself may have been too modest a person (we might say under-assertive) to claim her true position. More might come to light as research is done on the life and work of Marion Spielmann. brusselsbronte.blogspot.com/exhibition-and-lecture-at-museum-m-in.html

Spielmann, M.H., “Mlle. Louise Heger. Last link with the Brontës,” in The Times (

http://books.google.nl/books/Marion+Spielmann+bronte

Marion Harry Alexander Spielmann (1858–1948) was a prolific Victorian art critic and scholar who was the editor of The Connoisseur and Magazine of Art. Among his voluminous output, he wrote a history of Punch magazine, the first biography of John Everett Millais and a detailed investigation into the evidence for portraits of William Shakespeare. Spielmann was born in London May 22, 1858 and was educated at University College School andUniversity College, London. He soon established himself as an art journalist, writing for the Pall Mall Gazette from 1883 to 1890, most notably discussing the work of G. F. Watts.[1] By the 1880s, Spielmann had become "one of the most powerful figures in the late Victorian art world". Marion Spielmnn painted by John Henry Frederick Bacon.

I think this is the first time I've understood why Mme. Heger wanted the letters preserved...she wanted Charlotte to always be portrayed as a having a school girls crush, don't know why I never saw that before. I had always thought it strange that she mended the torn up letters...my eyes have been opened, thank you!!

BeantwoordenVerwijderenxo J~