While surving over internet I found on rictornorton ‘You tantalise me to death with talking of conversations by the fireside and between the blankets. Elizabeth Gaskell does not talk about "between the blankets" in "the life of Charlotte Bronte" and I don't read it in on Gutenberg "Charlotte and her circle"

I wonder: What did Charlotte really write in her letter to Ellen? Maybe a reader has the book of Margaret Smith with all Charlotte' s letters and can give me the answer?

I wonder: What did Charlotte really write in her letter to Ellen? Maybe a reader has the book of Margaret Smith with all Charlotte' s letters and can give me the answer?

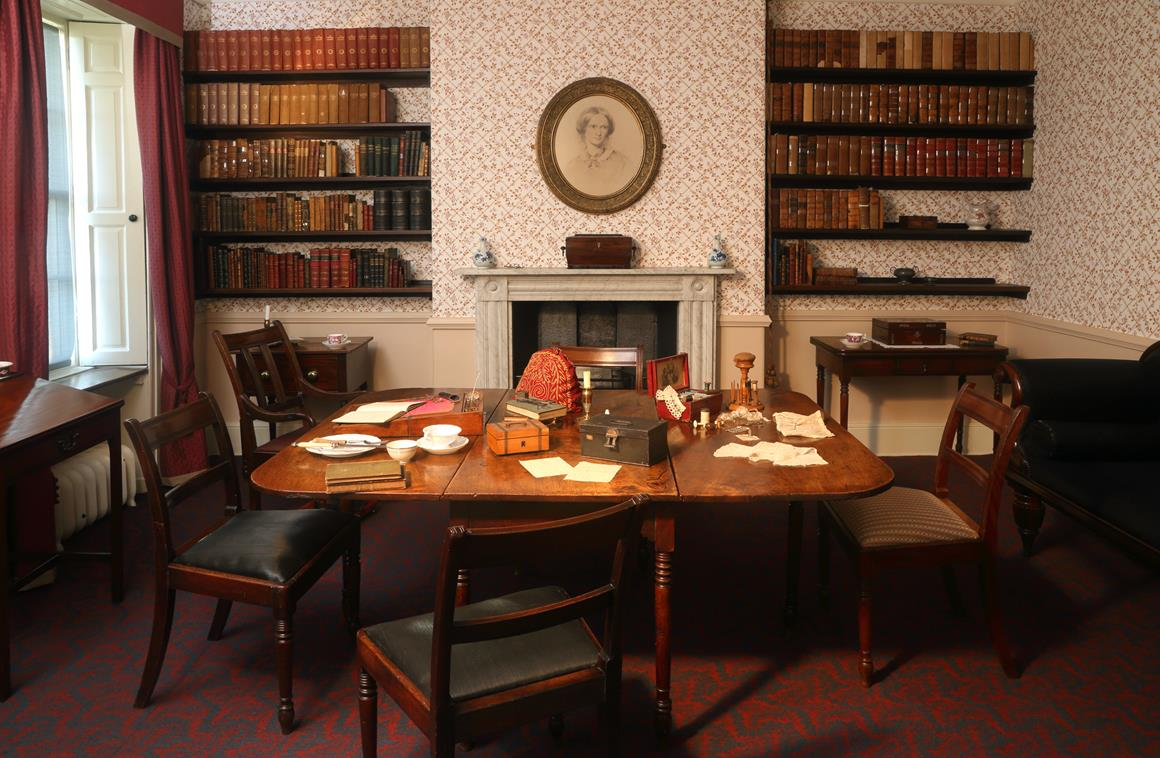

It is a commonplace for historians eager to dismiss the taint of homosexuality to point out that the sharing of beds was a very common practice until quite recent times ‘and no one ever thought anything of it’. Itis true that it was a very common practice, but it is also the case that people did think about it. Ellen Nussey and Charlotte Brontë always shared a bed at the vicarage at Haworth. Ellen tried to persuade Charlotte not to leave for Brussels to open a school, but to remain at home, and Charlotte replied on 20 January 1842: ‘You tantalise me to death with talking of conversations by the fireside and between the blankets.’ The words ‘and between the blankets’ were omitted from the official biography, by Elizabeth Gaskell who had become Charlotte’s friend only at the very end of her life. Since Mrs Gaskell (and Brontë’s husband) were sensitive to this issue in 1857, two years after Brontë’s death, it is clear that a queer view about sharing a bed was a contemporary possibility – not an anachronism of modern queer historians. rictornorton

January 20th, 1842. ‘Dear Ellen,—I cannot quite enter into your friends’ reasons for not permitting you to come to Haworth; but as it is at present, and in all human probability will be for an indefinite time to come, impossible for me to get to Brookroyd, the balance of accounts is not so unequal as it might otherwise be. We expect to leave England in less than three weeks, but we are not yet certain of the day, as it will depend upon the convenience of a French lady now in London, Madame Marzials, under whose escort we are to sail. Our place of destination is changed. Papa received an unfavourable account from Mr. or rather Mrs. Jenkins of the French schools in Brussels, and on further inquiry, an Institution in Lille, in the North of France, was recommended by Baptist Noel and other clergymen, and to that place it is decided that we are to go. The terms are fifty pounds for each pupil for board and French alone.

‘I considered it kind in aunt to consent to an extra sum for a separate room. We shall find it a great privilege in many ways. I regret the change from Brussels to Lille on many accounts, chiefly that I shall not see Martha Taylor. Mary has been indefatigably kind in providing me with information. She has grudged no labour, and scarcely any expense, to that end. Mary’s price is above rubies. I have, in fact, two friends—you and her—staunch and true, in whose faith and sincerity I have as strong a belief as I have in the Bible. I have bothered you both, you especially; but you always get the tongs and heap coals of fire upon my head. I have had letters to write lately to Brussels, to Lille, and to London. I have lots of chemises, night-gowns, pocket-handkerchiefs, and pockets to make, besides clothes to repair. I have been, every week since I came home, expecting to see Branwell, and he has never been able to get over yet. We fully expect him, however, next Saturday. Under these circumstances how can I go visiting? You tantalise me to death with talking of conversations by the fireside. Depend upon it, we are not to have any such for many a long month to come. I get an interesting impression of old age upon my face, and when you see me next I shall certainly wear caps and spectacles.—Yours affectionately,

‘C. B.’ Gutenberg Charlotte and her circle

‘C. B.’ Gutenberg Charlotte and her circle

According to Margaret Smith the letter says:

BeantwoordenVerwijderen"you bother & tantalize one to death with talking of converstations by the fireside or between the blankets depend upon it we are not to have any such - for many a long month to come - I get an interesting impression of old-age upon my face & when you see me next I shall certainly wear caps & spectacles."

The letter continues and is unsigned.

M.

BrontëBlog Team