So the highly successful 'Revisioning the Brontes' conference has now come to an end, and our soon-to-be new Director, Professor Ann Sumner, delivered the closing address.

This is what she said:

'We have had a fascinating cross-disciplin...ary conference today, reminding ourselves of the wide-ranging innovative artistic responses and interpretations of the Brontes' work and their enduring legacy within contemporary cultural society worldwide. We have been concentrating on revisioning, in other words refreshing and re-engaging with all aspects of the Brontes' lives, works, art and legacy.

Only yesterday we saw the media coverage surrounding the bicentenary of the publication of Jane Austen’s 'Pride and Prejudice', and as we move towards the bicentenary celebrations of Charlotte Bronte’s birth in 2016, a conference such as this inspires enthusiasts, fascinates scholars and academics and engages new and wide audiences breaking down fact from fiction.

Nick and Liz, the joint conference organisers must be praised for bringing together such a diverse and expert number of speakers today and for engaging with Leeds University students who have practically supported the conference. Partnership with the University of Leeds across disciplines and particularly with the Centre for Critical Studies in Museums, Galleries and Heritage is vital for us at the Bronte Society as we support and encourage the revisioning process.

Our day began with the atmospheric original music inspired by the lives and works of the Brontes and the landscape surrounding Haworth with David Wilson and the ‘Air on Bronte Moor’ which set the scene for a rich and fulfilling day ahead. Situated here in the impressive Brotherton Library, we have been surrounded all day by relevant archive material, and Sarah Prescott highlighted for us key manuscripts on show as well as outlining the history of the Bronte archive at the University, and how it was acquired by Brotherton and then the University.

Jane Sellars’ opening remarks considered the progress of Bronte studies in the widest sense over the past 20 years, reflecting on her own period as Director of the Parsonage Museum in the 1990s and her enthusiasm to engage a non-specialist audience as well as her own study of the art of the Brontes. She described the Museum when she arrived as a shrine, and its gradual transformation into a place of genuine inspiration for all creative subjects while still remaining a place of pilgrimage today for visitors from all over the world. There followed a number of fascinating papers.

Carl Plasa decided to revise his own paper and retitle it before he had even started (!) and concentrated initially on the role of Bertha Mason in 'Jane Eyre', followed by an interesting discussion of Kate Chopin’s 'At Fault'. Amber Poulliot then considered in depth the inter-war fictional biographies which applied psychoanalysis to literary criticism to explain how such sisters could write such novels. Alslim Hunter gave a thought-provoking explanation of how our brains respond to a resonant experience, the power of the authentic object and the role of familiarity in informing our response to a genuine artefact (specifically she mentioned various locks from famous heads of hair!, as well as the secondary resonance of contemporary artists' interventions such as Cornelia Parker’s photograph of Anne Bronte’s handkerchief.

Sarah Wootton gave an excellent assessment of Paula Rego’s lithographs responding to 'Jane Eyre' while not ever glamorising the heroine, her discussion included an interesting assessment of ‘Loving Bewick’, and she emphasised the fact that there is no one image of Jane or no fixed viewpoint in the series. The contemporary artist Lisa Sheppy gave an account of what had inspired her piece 'Charlotte’s Dress', currently on display in the 'Wilderness Between the Lines' exhibition at the Leeds College of Art. It was an early childhood visit to the Parsonage and memories of her mother’s professional dressmaking days that had given her the initial idea for the piece. To hear directly from an artist about her creative process was inspiring, and seeing her sketches from her study visit to Haworth and learn about the makers who had added to that vision and enabled her to produce this striking work was illuminating, but also caused one to reflect on the strong influence of her mother on the piece, while Charlotte Bronte had lost her own mother young.

Then there was Jenny Bavidge’s excellent paper on the grandiose and epic musical film tracks from various productions of 'Wuthering Heights' films over the years: a novel, she pointed out to us, which actually contained little musical reference. This was followed by a paper which covered the history of the reception of 'Wuthering Heights' in Japan, where it was first translated in the late 1890s but which only became popular in the 1940s after the Hollywood film; and there was a contextualisation of the 1988 Arashi ga Oka film which was nominated for a Palm d’Or that year. One of the highlights of the day was Richard Brown’s sensitive and witty interviewing of Blake Morrison, where we sorted out fact from fiction in the play 'We are Three Sisters', and heard about the research and writing of the play.

A lively round-table debate focused on the timeless quality of the landscape around Haworth while acknowledging the many calls upon the landscape today, why Emily Bronte wrote 'Wuthering Heights' and how a new generation now came to the novel through Bella and Edward’s admiration for it in the 'Twilight' series.

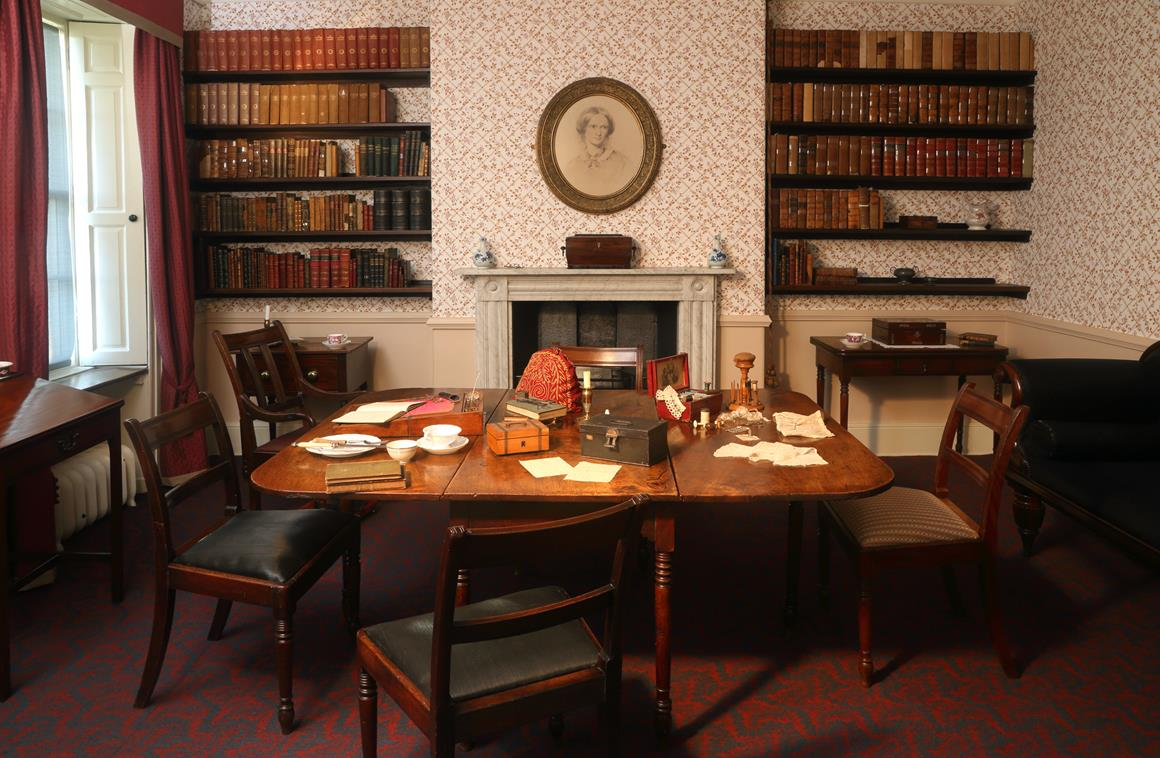

This conference comes at a crucial moment with two key exhibitions mounted here in Leeds at the very same time that the Bronte Society is undertaking a refurbishment of the Parsonage Museum - the first in 25 years - based on scientific and historical analysis carried out by the University of Lincoln, and advised by historical interior designer Allyson McDermott, so that the interiors will be transformed and areas will reflect the ‘facelift’ Charlotte gave the home in the 1850s when she spent some of her income from the publication of her novels.

The redecoration scheme has inspired our exhibition this year and is at the heart of our Contemporary Arts Programme. We hope the ‘new look’ Parsonage will inspire not only more visitors but the continued interest of writers, musicians , artists and creative thinkers who will respond anew to the Bronte legacy.

I take up my new post officially at the end of next week and will begin working with the team on the bicentenary programme for 2016. I have myself been fascinated by the many paintings which have adorned the covers of paperback editions of the Bronte novels, and am showing you this famous image of the Augustus Egg painting 'Travelling Companions' at Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery, which I used to walk past each day. This is the cover illustration of the Everyman edition of 'Jane Eyre', and seems to me a rather odd choice, painted some 15 years after the novel was published. To me it will always be Francis Grant’s more restrained 'Portrait of Mary Isabella Grant' of c 1850 in Leicester which epitomises the heroine, because it was on my 1975 paperback as a girl studying for O-levels. I feel a paper coming on... And as Nick said earlier, this could well have been a two-day conference.

I do so hope that the Bronte Society will work again with the University of Leeds and that Nick will ask us back. We would like to follow this up with study days and a major conference in 2016. The Bronte Society is committed to this process, and if you are not already a member or your membership has lapsed, do please pick up a form to renew as you leave! Or sign up for our enewsletter and please follow us on Facebook! facebook/Bronte-Parsonage-Museum

This is what she said:

'We have had a fascinating cross-disciplin...ary conference today, reminding ourselves of the wide-ranging innovative artistic responses and interpretations of the Brontes' work and their enduring legacy within contemporary cultural society worldwide. We have been concentrating on revisioning, in other words refreshing and re-engaging with all aspects of the Brontes' lives, works, art and legacy.

Only yesterday we saw the media coverage surrounding the bicentenary of the publication of Jane Austen’s 'Pride and Prejudice', and as we move towards the bicentenary celebrations of Charlotte Bronte’s birth in 2016, a conference such as this inspires enthusiasts, fascinates scholars and academics and engages new and wide audiences breaking down fact from fiction.

Nick and Liz, the joint conference organisers must be praised for bringing together such a diverse and expert number of speakers today and for engaging with Leeds University students who have practically supported the conference. Partnership with the University of Leeds across disciplines and particularly with the Centre for Critical Studies in Museums, Galleries and Heritage is vital for us at the Bronte Society as we support and encourage the revisioning process.

Our day began with the atmospheric original music inspired by the lives and works of the Brontes and the landscape surrounding Haworth with David Wilson and the ‘Air on Bronte Moor’ which set the scene for a rich and fulfilling day ahead. Situated here in the impressive Brotherton Library, we have been surrounded all day by relevant archive material, and Sarah Prescott highlighted for us key manuscripts on show as well as outlining the history of the Bronte archive at the University, and how it was acquired by Brotherton and then the University.

Jane Sellars’ opening remarks considered the progress of Bronte studies in the widest sense over the past 20 years, reflecting on her own period as Director of the Parsonage Museum in the 1990s and her enthusiasm to engage a non-specialist audience as well as her own study of the art of the Brontes. She described the Museum when she arrived as a shrine, and its gradual transformation into a place of genuine inspiration for all creative subjects while still remaining a place of pilgrimage today for visitors from all over the world. There followed a number of fascinating papers.

Carl Plasa decided to revise his own paper and retitle it before he had even started (!) and concentrated initially on the role of Bertha Mason in 'Jane Eyre', followed by an interesting discussion of Kate Chopin’s 'At Fault'. Amber Poulliot then considered in depth the inter-war fictional biographies which applied psychoanalysis to literary criticism to explain how such sisters could write such novels. Alslim Hunter gave a thought-provoking explanation of how our brains respond to a resonant experience, the power of the authentic object and the role of familiarity in informing our response to a genuine artefact (specifically she mentioned various locks from famous heads of hair!, as well as the secondary resonance of contemporary artists' interventions such as Cornelia Parker’s photograph of Anne Bronte’s handkerchief.

Sarah Wootton gave an excellent assessment of Paula Rego’s lithographs responding to 'Jane Eyre' while not ever glamorising the heroine, her discussion included an interesting assessment of ‘Loving Bewick’, and she emphasised the fact that there is no one image of Jane or no fixed viewpoint in the series. The contemporary artist Lisa Sheppy gave an account of what had inspired her piece 'Charlotte’s Dress', currently on display in the 'Wilderness Between the Lines' exhibition at the Leeds College of Art. It was an early childhood visit to the Parsonage and memories of her mother’s professional dressmaking days that had given her the initial idea for the piece. To hear directly from an artist about her creative process was inspiring, and seeing her sketches from her study visit to Haworth and learn about the makers who had added to that vision and enabled her to produce this striking work was illuminating, but also caused one to reflect on the strong influence of her mother on the piece, while Charlotte Bronte had lost her own mother young.

Then there was Jenny Bavidge’s excellent paper on the grandiose and epic musical film tracks from various productions of 'Wuthering Heights' films over the years: a novel, she pointed out to us, which actually contained little musical reference. This was followed by a paper which covered the history of the reception of 'Wuthering Heights' in Japan, where it was first translated in the late 1890s but which only became popular in the 1940s after the Hollywood film; and there was a contextualisation of the 1988 Arashi ga Oka film which was nominated for a Palm d’Or that year. One of the highlights of the day was Richard Brown’s sensitive and witty interviewing of Blake Morrison, where we sorted out fact from fiction in the play 'We are Three Sisters', and heard about the research and writing of the play.

A lively round-table debate focused on the timeless quality of the landscape around Haworth while acknowledging the many calls upon the landscape today, why Emily Bronte wrote 'Wuthering Heights' and how a new generation now came to the novel through Bella and Edward’s admiration for it in the 'Twilight' series.

This conference comes at a crucial moment with two key exhibitions mounted here in Leeds at the very same time that the Bronte Society is undertaking a refurbishment of the Parsonage Museum - the first in 25 years - based on scientific and historical analysis carried out by the University of Lincoln, and advised by historical interior designer Allyson McDermott, so that the interiors will be transformed and areas will reflect the ‘facelift’ Charlotte gave the home in the 1850s when she spent some of her income from the publication of her novels.

The redecoration scheme has inspired our exhibition this year and is at the heart of our Contemporary Arts Programme. We hope the ‘new look’ Parsonage will inspire not only more visitors but the continued interest of writers, musicians , artists and creative thinkers who will respond anew to the Bronte legacy.

I take up my new post officially at the end of next week and will begin working with the team on the bicentenary programme for 2016. I have myself been fascinated by the many paintings which have adorned the covers of paperback editions of the Bronte novels, and am showing you this famous image of the Augustus Egg painting 'Travelling Companions' at Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery, which I used to walk past each day. This is the cover illustration of the Everyman edition of 'Jane Eyre', and seems to me a rather odd choice, painted some 15 years after the novel was published. To me it will always be Francis Grant’s more restrained 'Portrait of Mary Isabella Grant' of c 1850 in Leicester which epitomises the heroine, because it was on my 1975 paperback as a girl studying for O-levels. I feel a paper coming on... And as Nick said earlier, this could well have been a two-day conference.

I do so hope that the Bronte Society will work again with the University of Leeds and that Nick will ask us back. We would like to follow this up with study days and a major conference in 2016. The Bronte Society is committed to this process, and if you are not already a member or your membership has lapsed, do please pick up a form to renew as you leave! Or sign up for our enewsletter and please follow us on Facebook! facebook/Bronte-Parsonage-Museum

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten