18 July 2017 is a special day for literature aficionados across the globe, for it marks the 200th anniversary of the death of perhaps the most beloved writer of them all: Jane Austen.

Women like Elizabeth Gaskell, George Eliot, and especially the Brontë sisters. Charlotte, Emily and Anne are in the middle of 200th anniversaries of their own, as we remember the bicentenaries of their births in the years 1816 to 1820. Along with Austen they crafted brilliant works of genius that are the equal of any novels written by men, and in the public’s eye the Brontës and Jane have become inextricably linked.

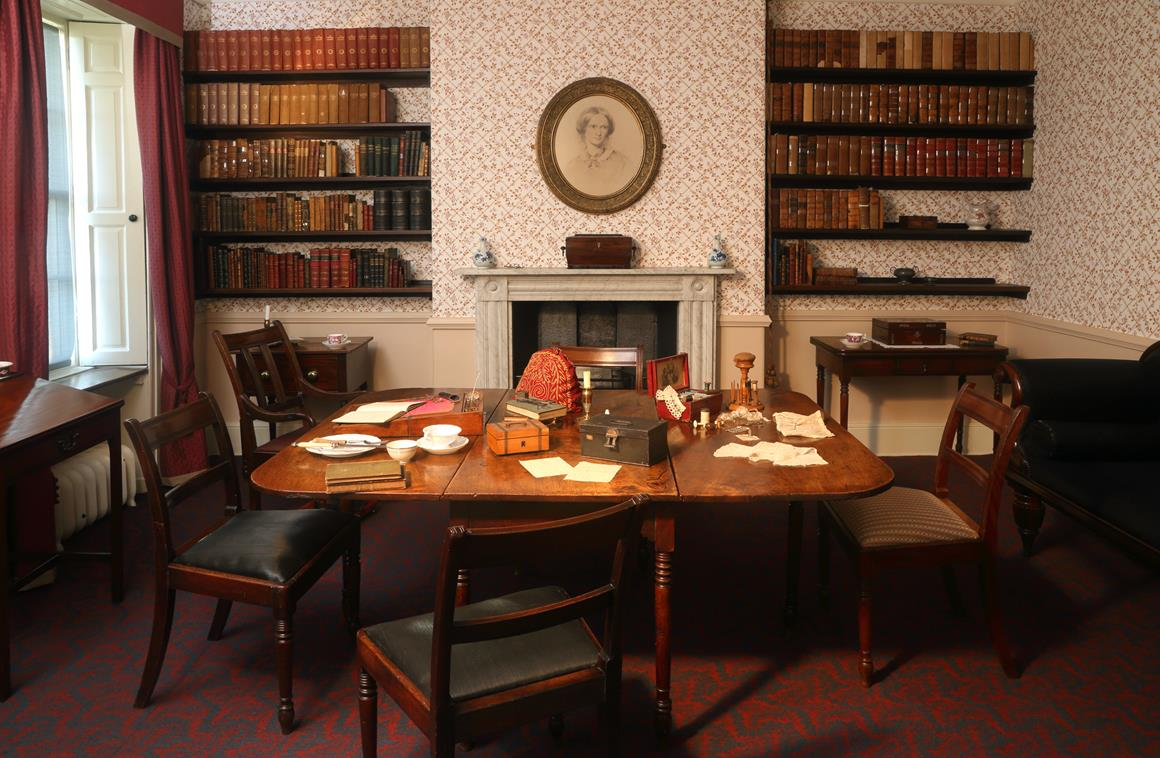

I once asked one of the hard-working guides at the Brontë Parsonage Museum in Haworth what question they are asked more than any other. It was ‘Which of the Brontë sisters wrote Pride and Prejudice?’ followed closely by, ‘Is this where Jane Austen wrote her novels?’

It’s easy to see why the four writers should become mixed in the public’s perception. On a superficial level there are some similarities between Jane and the Brontës: Jane was after all an early nineteenth century writer who never married and lived with her family throughout her life. So far, so similar with Anne, Emily and Charlotte (who, admittedly, did marry aged 38, only to succumb to the effects of excessive morning sickness and die less than a year later). In other ways, however, Jane was very different to the Yorkshire triumvirate.

Jane was writing earlier in the century than the Brontës, and in a century that changed so radically as the decades advanced, this made a huge difference. Jane Austen was very much a regency woman, familiar with the values and traditions of the late eighteenth century, whereas the Brontës grew up at the start of Queen Victoria’s reign, and witnessed the huge social impact brought by the industrial revolution in a way that Jane never did. As an example of this, Jane Austen travelled to London from Chawton, in Hampshire, in 1815 by horse drawn carriage. In 1848, Charlotte and Anne Brontë travelled from Keighley to London via train.

The purpose of these two meetings reveals another important difference between Jane Austen and the Brontë sisters: Jane was travelling to meet the Prince Regent, later George IV, who was a huge fan of her work; Charlotte and Anne Brontë were travelling to meet the publisher George Smith, where they would finally reveal their true identity away from the masks of Currer and Acton Bell that they had hidden behind.

Jane Austen’s writing made her famous in her lifetime, a success that Anne and Emily would never know or desire. The Brontë sisters needed money in a way that Jane never did, but they eschewed fame and preferred public anonymity, although after the death of her younger sisters Charlotte did, reluctantly, step into the limelight.

Another important distinction between Jane Austen and the Brontë sisters was their social position. Whilst the Brontës were respectable, thanks to their father Patrick’s position as a long established priest in the Church of England, they were never rich, and were solidly lower middle class, whereas Jane was from an upper middle class background. Her financial position, and her position in society, became even more secure when her brother Edward was adopted by the very wealthy Thomas Knight. Knight had no children of his own, and in 1783 chose his distant relative the 15 year old Edward Austen, afterwards Edward Austen Knight, to be his legal heir. Edward adopted a number of grand properties, including the beautiful Chawton House. He also obtained a nearby property at Chawton for Jane to live in, and it was there that she worked on some of her greatest masterpieces.

The contrast between Jane’s brother Edward and the Brontës’ brother Branwell could not be greater: Branwell seemed to be a promising talent in his own right, but there would be no wealthy patronage for him, and he died at the age of 31 after a long addiction to drink and opium.

Other than their brilliant writing, there is one striking similarity between Jane Austen and the Brontës: sisterly love. Emily and Anne Brontë in particular were very close, being referred to as being like inseparable twins, despite their age difference. A similar relationship existed between Jane Austen and her sister Cassandra, two years older than Jane and always by her side throughout her life.

In the 200 years since her death, Jane Austen’s reputation has grown, but just what did Charlotte Brontë think of her? In fact, Charlotte reported that she had never read Jane Austen’s work until she was urged to by the critic G. H. Lewes. She was far from impressed as we can see from her reply to Lewes:

‘Why do you like Miss Austen so very much? I am puzzled on that point... I had not seen Pride & Prejudice till I read that sentence of yours, and then I got the book and studied it. And what did I find? An accurate daguerreotyped portrait of a common-place face; a carefully-fenced, highly cultivated garden with neat borders and delicate flowers - but no glance of a bright vivid physiognomy - no open country - no fresh air - no blue hill - no bonny beck. I should hardly like to live with her ladies and gentlemen in their elegant but confined houses.’

Charlotte’s judgement should be seen in the light of her irritation that Jane Eyre was being compared to Austen novels. It was a fate that befell Anne Brontë’s first novel too, as we see from the following extract from a review: ‘Agnes Grey is a somewhat coarse imitation of one of Miss Austin’s charming stories.’ It’s a pity, of course, that the reviewer hadn’t found the stories so charming that he’d remembered how to spell Miss Austen’s name.

If we take a more dispassionate look than Charlotte did, we simply have to acknowledge that Jane Austen’s books are works of genius just like those of herself and her sisters. One early twentieth century writer, however, thought it was unfair that Anne Bronte in particular was being overlooked in favour of Jane Austen. In 1924, celebrated Irish author George Moore wrote:

‘If Anne Brontë had lived ten years longer, she would have taken a place beside Jane Austen, perhaps even a higher place.’

We can equally lament that Jane Austen did not live another ten years. Her novels will always be read and always be loved. While ever this planet of ours continues its restless orbit around the sun, readers will still swoon over Mr Darcy and root for Emma to find her Knightley. Times will change, but the novels of Jane Austen will remain timeless. On this special day, we should all give a silent thanks to Jane Austen for her novels, and her ground-breaking role in the history of literature.

By Nick Holland. Author of

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten