Politically a Tory, she preached tolerance rather than revolution. She held high moral principles and, despite her shyness, was prepared to argue for her beliefs.

------------------------------------------------------

Tory refers to those holding a political philosophy (Toryism) commonly regarded as based on a traditionalist and conservative view which grew out of the Cavalier faction in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. It is a prominent ideology in the politics of the United Kingdom. English Tories from the time of the Glorious Revolution up until the Reform Bill of 1832 were characterized by strong monarchist tendencies, support for the Church of England, and hostility to reform, while the Tory Party was an actual organization which held power intermittently throughout the same period.[11] Since 1832, the term "Tory" is commonly used to refer to the Conservative Party and its members. wiki/Tory

The Conservative Party traces its origins to a faction, rooted in the 18th-century Whig Party, that coalesced around William Pitt the Younger (Prime Minister of Great Britain 1783–1801 and 1804–1806). Originally known as "Independent Whigs", "Friends of Mr Pitt", or "Pittites", after Pitt's death the term "Tory" came into use. This was an allusion to the Tories, a political grouping that had existed from 1678, but which had no organisational continuity with the Pittite party. From about 1812 on the name "Tory" was commonly used for the newer party. wiki/Conservative_Party

Besides Mary Taylor's deep friendship with Charlotte Bronte, there are many other motivations to read this fascinating novel. Mary Taylor is wonderful at descriping the working class as complex and interesting characters and her politics are more radical than Charlotte's. Taylor manages to capture the Yorkshire dialect without snobishness. Charlotte was a political Tory/conservative and could often write harsly of the poor working class struggle for equality and respect (see her novel Shirley). And for anyone who has studied Victorian feminism, this novel is a great reflecting point. It's a shame that Mary Taylor did NOT save her letters from Charlotte nor hand them over to biographer and fellow Victorian novelist aElizabeth Gaskell, because the intellectual and literary discussions the two writers would have engaged in would have been fascinating to read -- especially their positions on women's education, marriage, children, and careers. Miss-Miles-Tale-Yorkshire-Years

------------------------------------------------------

The Taylors were an old and respected, but unconventional, Yorkshire textiles family. The six children were encouraged by their father, a fierce radical in religion and politics, to develop independence of thought and action and freedom of expression.

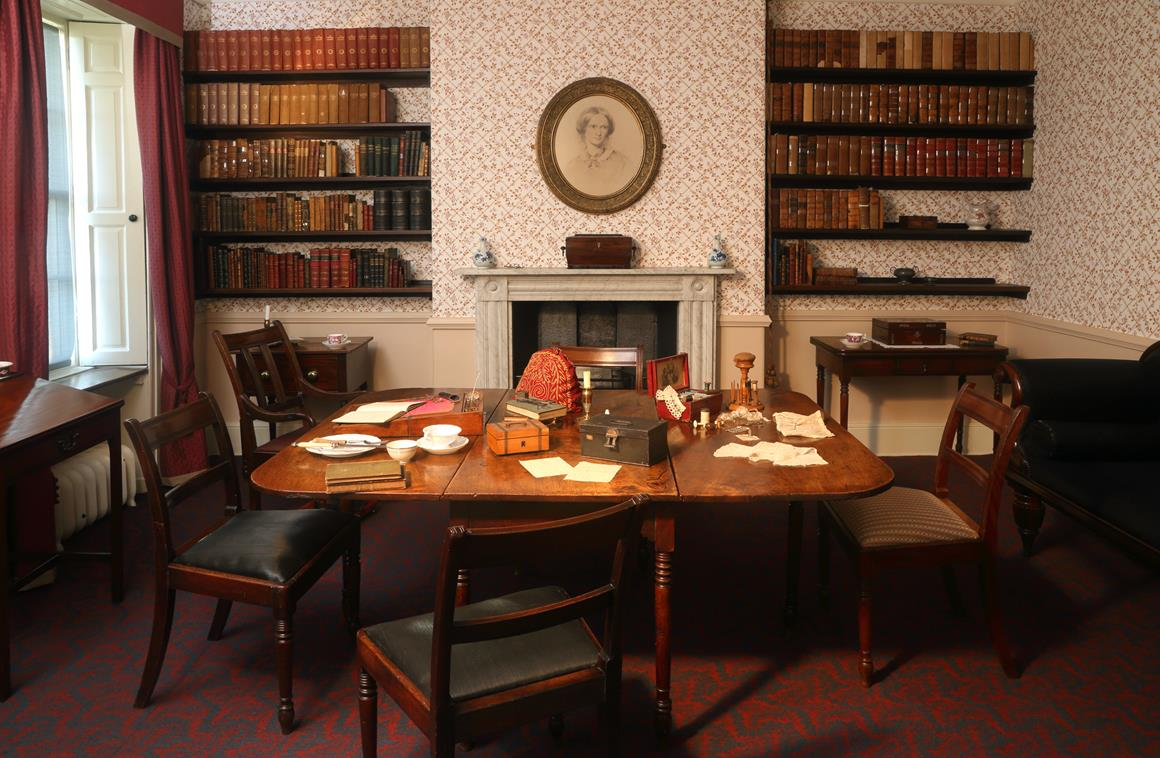

Joshua Taylor was an educated, cultured and strongly cosmopolitan influence upon them. The Taylors exported cloth to Europe and America and had strong European connections. They often travelled in Europe on business and pleasure and had relatives living in Brussels. In the 1830s Charlotte Brontë sometimes stayed at Red House. She greatly enjoyed her visits, writing that:

‘… the society of the Taylors is one of the most rousing

leasures I have ever known.’ (Charlotte Brontë to Ellen Nussey, 15 April 1839)

Mary Taylor later wrote about Charlotte’s visits:

‘We used to dispute about politics and religion. She, a Tory and clergyman’s daughter, was always in a minority of one in our house of violent Dissent and Radicalism.’ (Mary Taylor to Mrs Gaskell, 1856) RedHouse-MaryTaylor

----------------------------------

Tory refers to those holding a political philosophy (Toryism) commonly regarded as based on a traditionalist and conservative view which grew out of the Cavalier faction in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. It is a prominent ideology in the politics of the United Kingdom. English Tories from the time of the Glorious Revolution up until the Reform Bill of 1832 were characterized by strong monarchist tendencies, support for the Church of England, and hostility to reform, while the Tory Party was an actual organization which held power intermittently throughout the same period.[11] Since 1832, the term "Tory" is commonly used to refer to the Conservative Party and its members. wiki/Tory

Indeed, I morn Mary's lost letters as much as Charlotte's in that exchange. Just the few of Mary's letters we have show an intelligence a forthrightness and a wit which stood alone in Charlotte's world until she started moving in London circles. ...and I would argue as to whether she found in effect any one better in those regards even then . In her way Mary was up to CB's best mentally ...and that was very rare in Charlotte's experience

BeantwoordenVerwijderenMr. Bronte's Toryism stemmed, I believe, from his experience in Ireland as a youth. He bettered himself in the system, why could not others? .But more, he saw what lawlessness can do in rebellion and how it can call forth even more oppression.

In such a case one would likely uphold the law as the best of a bad lot and seek change though reform, which we know he did his whole life in a vigorous manner.

Politically, Charlotte is often not sympathetic to the modern reader. When factory workers won a case against a criminal owner, she wrote to her father she was glad of course, but unhappy too since such events make the " lower orders "( a term she constantly uses about the working class ) unhappy with their lot and less likely to work.

lol It's little wonder Charlotte passed on composing the social change type of novel and yet who stood more for freedom of self?

Sitting at the Taylor table must of been a revelation to Charlotte, not having heard such arguments before and certainly never so forcibly lol

Again, one must look to Rev Bronte's commitment to mental freedom for his children. How many others would have snatched Charlotte away and forbidden such company?

Yet the Taylors became like family

The differences between Charlotte and her husband , Arthur Bell Nichols, are often highlighted. But they were in accord in their conservatism and in their dry humor...powerful bonds .

It's to be remembered Charlotte did not submit to his views , in the most part she agreed with them ( expect for his attitude to Dissenters! lol! )

Despite the dazzling figure of Shirley Keeldar, though, the novel is fundamentally anti-idealistic. Its anti-Utopian stance sets it in a line of Tory pessimism going right back to Swift and Dr Johnson..

An astute observation. Dr. Johnson was another one who had dim views of upsetting the social order. But like Charlotte, he had great sympathy for individuals who found themselves in difficulties within that order .

Basically the idea is humans are rascals...lol

Near the end of Charlotte's life the Crimea war broke out . In a letter to Miss Wooler Charlotte expressed a different feeling about such matters that she had held before which she saw as a result of middle age approaching...the flowing sword of justice was slipping from her hand and she saw more the human cost. One can only wonder how else time and life would have modify her views or not ...

Mary & Charlotte's letters to each other would have been so fascinating to read, truly a shame that Mary chose to burn them, such a loss. I would have loved to have been a fly on the wall at the Taylor's when charlotte was there. Invigorating and lively political and social discussions, such as she was used to at home, I'm sure felt very normal to her, unlike those she most likely had at Brookroyd, which were most likely very proper and polite, and not at all 'course'.

BeantwoordenVerwijderenxo J~

Yes, I wished as well that I lived in that time and could meet them and talk with them and be part of their circle.

BeantwoordenVerwijderenI as well wished Mary saved her letters. What would we learn about Charlotte?