From Independent: She is best known for the gentle, humorous exploits of the gossiping women of Cranford, which Dame Judi Dench and co popularly brought to life on the small screen.

Yet so controversial was another of Elizabeth Gaskell’s novels to her Victorian readers that it was banned in many households, including her own, being, as she described it, “not a book for young people”. The hostile reaction to Ruth, her 1853 story that has as its heroine a working-class teenage girl who is seduced and abandoned as an unmarried mother, made the writer ill. “I think I must be an improper woman without knowing it, I do so manage to shock people,” she wrote to her friend, Eliza Fox. “Now should you have burnt the 1st vol. [sic] of Ruth as so very bad? Even if you had been a very anxious father of a family? Yet two men have; and a third has forbidden his wife to read it; they sit next to us in chapel and you can’t think how ‘improper’ I feel under their eyes.”

She was not afraid, however, of raising important social issues through her work. While in Ruth she confronts Victorian attitudes to illegitimacy and the “fallen woman”, her first book, the 1848 industrial novel Mary Barton, had tackled topics including drugs, poverty, the relationship between employer and employee, and the Chartist movement. “Writing was Gaskell’s most effective form of philanthropy”, says Jenny Uglow in her biography of the novelist, Elizabeth Gaskell: A Habit of Stories.

While in the past, “Mrs Gaskell”, as she was known, was often, misleadingly, presented as the perfect housewife, it now appears that there was much more to the author than domesticity. The Manchester Historic Buildings Trust will highlight her status as one of the 19th century’s most important women writers when it opens the doors to her newly restored former Manchester home next week. With displays of artefacts and manuscripts, and a programme of events, the house will become a centre for the understanding of the Gaskell family’s literary and cultural heritage.

Thanks to a £2.5m renovation, part-financed by a Heritage Lottery Fund grant, visitors to 84 Plymouth Grove will be able to experience for the first time the suburban villa and its re-established Victorian gardens as they might have appeared during Gaskell’s lifetime. They will follow in some rather famous footsteps: the sociable author was a “networker par excellence”, according to Janet Allan, chair of the trust set up in 1998 with the aim of saving Gaskell’s Grade II*-listed house.

The restored drawing room houses a piano similar to that on which Charles Hallé, the conductor and founder of Manchester’s Hallé orchestra, gave music lessons to Gaskell’s daughters. It is in the same room that a shy Charlotte Brontë hid behind the curtains to avoid seeing guests. Other esteemed visitors over the years included Harriet Beecher Stowe, the American abolitionist and author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, and the art critic John Ruskin, not to mention Gaskell’s editor, a certain Charles Dickens.

Born in London in 1810, Gaskell moved the following year, after the death of her mother, to live with her aunt, Hannah Lumb, in the Cheshire town of Knutsford, which would later provide the inspiration for Cranford. Marriage took her to Manchester in 1832.

She lived in Plymouth Grove between 1850 and her death in 1865, a period during which she wrote the popular novels Cranford, Ruth and North and South, the lesser-known Sylvia’s Lovers, and the unfinished Wives and Daughters. She and her husband, William, a Unitarian minister at the city’s Cross Street Chapel, wanted space and fresh air for their four daughters and, when they moved in, the house lay near open fields. Brontë remarked in a letter, in 1951, to her publisher, George Smith, that it was “a large, cheerful, airy house, quite out of Manchester smoke”.

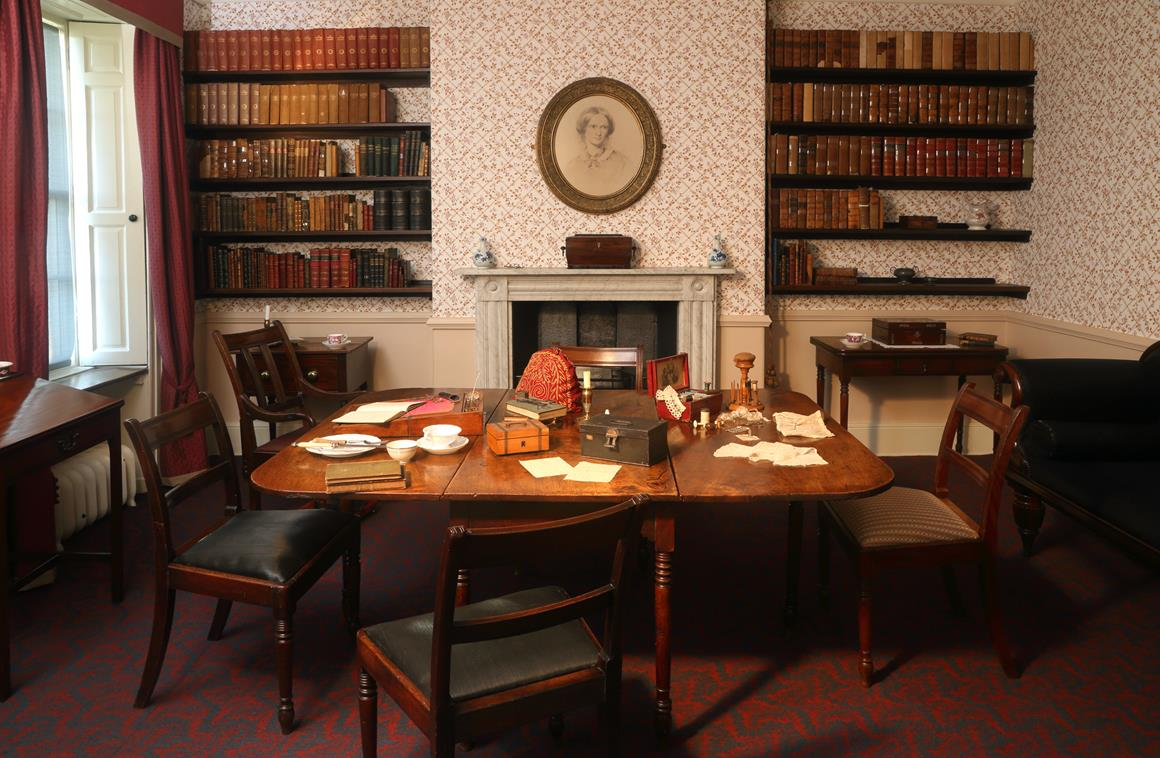

While William worked in his study – in which visitors to the house will see the original bookcases filled with period titles researchers think the family might have read – his wife fitted her writing around the running of the household and, no doubt, disruptions from the morning room used as the girls’ nursery. Without a room of her own, she used to pen wonderfully gossipy letters, and parts of her novels, sitting at a small table in the dining-room window overlooking the garden she so loved.

Elizabeth Gaskell's dining room and table from which she wrote her novels (Photo Joel Chester Fildes. Press image from Catharine Braithwaite)

There were times, however, when Lily, as she was known to her family, sought out places to write away from her domestic responsibilities and Manchester. As the passport on display testifies, she was a keen traveller, often with a daughter in tow but usually without her husband, who liked being in the city. “He [William] must have been quite an indulgent husband because she spent an enormous amount of time not at home at all,” says Ms Allan. “There was one year when for almost half the year she wasn’t here. She was whizzing around doing all sorts of other things.” As soon as she had finished writing the biography of her friend, Brontë, in 1857, for instance, she escaped to Rome and so it was William who had to pick up the pieces and deal with the ensuing libel case. The couple were on “parallel tracks” that didn’t always merge, says Ms Allan. While William used to spend holidays with Beatrix Potter’s family, Elizabeth and the girls would go elsewhere. “But it didn’t mean they were at odds with each other,” she adds. “I think it was a very supportive relationship.”

Ms Allan says that, for a long time, the writer was pigeon-holed as “Mrs Gaskell”, the author of Cranford, a work which she claims has a “much more profound emotional element to it” than some people might appreciate, dealing as it does with the position of single women and how they make a life for themselves and manage to circumvent tragedies in their lives.

“It’s only in the past 25 years that her reputation has grown and she’s recognised as a very professional, courageous novelist, who was prepared to write about really difficult issues,” she adds. “I think Cranford, although it is a wonderful book, has in a way done her a great disservice because people just think it’s about silly old ladies in bonnets and I’m afraid that’s been confirmed by the [BBC] television version. There’s a lot more to it than that, and a lot more to her.”

Elizabeth Gaskell’s House re-opens to the public on Sunday, 5 October. Visit www.elizabethgaskellhouse.co.uk

Geen opmerkingen:

Een reactie posten