My love of the Brontë Family – I have written this for my Dad, as it was he who sparked my interest many years ago. From: Write on Ejaleigh

It’s my birthday and wedding anniversary next week and I’ll be making my way to Haworth where I shall be staying at the Old Registry and visiting for the umpteenth time, the Brontë Parsonage Museum. My husband says that my face always lights up when we get our first glimpse of the Parsonage and that he has never seen me so happy as I am when I am there. I’m currently rereading Wuthering Heights as this year is the bicentenary of Emily’s birth. There’s been a bit of controversy in the Brontë Society too over the appointment of a literary partner. However, this has led to more interest than ever in the Brontë Family. But where did my love for the Brontë family begin and how has it remained so passionate for the past forty-odd years?

In the early 1960s, my Dad was taken on a school trip to Haworth and to the Brontë Parsonage Museum. He tells me that in those days the Brontë Industry had yet to take off and Haworth was very much as it was during the Brontë era. My Dad, a practical man, who had failed his 11+ and had to go to a secondary modern school, was transfixed by what he saw at the Parsonage. He found the story of how three sisters, living in such a remote location, became famous novelists, fascinating and it is true to say that he instantly resolved to discover more about them and read their works

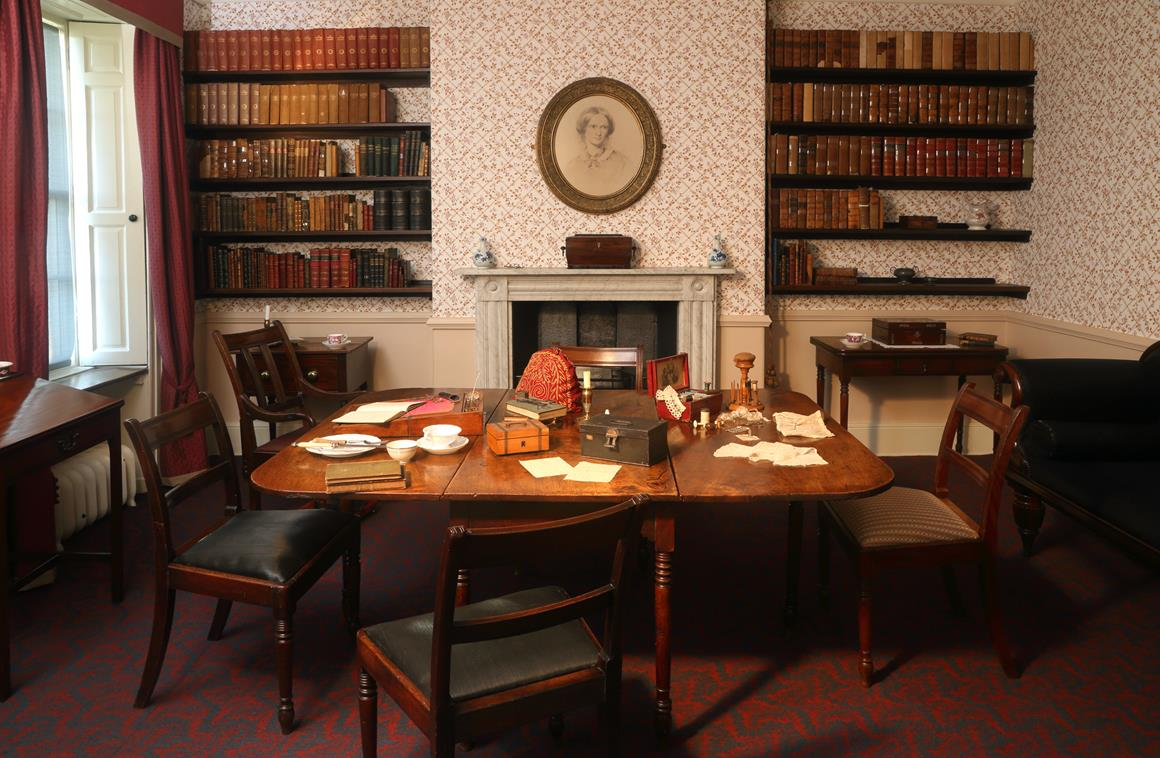

Fast forward to the early 1970s, and when my Dad passed his driving test, he decided to take my Mother, my brother and I, to visit the same location where he had been inspired to discover more about the Brontë Family. I can vividly recall my first visit to the Parsonage, although I must have been only about three years of age. My parents later told me that, as we went around the Parsonage, I was able to tell them the contents of each room and what they signified, even though I had never been there before. My Mother took this as a spiritual sign that I had been ‘on this earth before’. My Father was more pragmatic and suggested that I was probably savvier than they had realised and had looked up the place in his AA Treasures of Britain book and managed to read some of it. I really have no idea where it came from but all I knew was that going there always felt like I was going somewhere I loved and where I felt happy. You can read into that whatever you like. In those days, it was possible to see the Bonnell collection on display of many of the Brontë juvenilia. These tiny books transfixed me, and I decided that I was going to make my own tiny books at home. Yet much like my Dad, it had been the tragic nature of their lives that had really touched me.

It’s my birthday and wedding anniversary next week and I’ll be making my way to Haworth where I shall be staying at the Old Registry and visiting for the umpteenth time, the Brontë Parsonage Museum. My husband says that my face always lights up when we get our first glimpse of the Parsonage and that he has never seen me so happy as I am when I am there. I’m currently rereading Wuthering Heights as this year is the bicentenary of Emily’s birth. There’s been a bit of controversy in the Brontë Society too over the appointment of a literary partner. However, this has led to more interest than ever in the Brontë Family. But where did my love for the Brontë family begin and how has it remained so passionate for the past forty-odd years?

In the early 1960s, my Dad was taken on a school trip to Haworth and to the Brontë Parsonage Museum. He tells me that in those days the Brontë Industry had yet to take off and Haworth was very much as it was during the Brontë era. My Dad, a practical man, who had failed his 11+ and had to go to a secondary modern school, was transfixed by what he saw at the Parsonage. He found the story of how three sisters, living in such a remote location, became famous novelists, fascinating and it is true to say that he instantly resolved to discover more about them and read their works

Fast forward to the early 1970s, and when my Dad passed his driving test, he decided to take my Mother, my brother and I, to visit the same location where he had been inspired to discover more about the Brontë Family. I can vividly recall my first visit to the Parsonage, although I must have been only about three years of age. My parents later told me that, as we went around the Parsonage, I was able to tell them the contents of each room and what they signified, even though I had never been there before. My Mother took this as a spiritual sign that I had been ‘on this earth before’. My Father was more pragmatic and suggested that I was probably savvier than they had realised and had looked up the place in his AA Treasures of Britain book and managed to read some of it. I really have no idea where it came from but all I knew was that going there always felt like I was going somewhere I loved and where I felt happy. You can read into that whatever you like. In those days, it was possible to see the Bonnell collection on display of many of the Brontë juvenilia. These tiny books transfixed me, and I decided that I was going to make my own tiny books at home. Yet much like my Dad, it had been the tragic nature of their lives that had really touched me.

I remember keeping my special entrance ticket and my Mother also bought me a Charlotte Brontë bookmark which had a poem on it;

Life, believe, is not a dream

So dark as sages say;

Oft a little morning rain

Foretells a pleasant day.

Sometimes there are clouds of gloom,

But these are transient all;

If the shower will make the roses bloom,

O why lament its fall?

So dark as sages say;

Oft a little morning rain

Foretells a pleasant day.

Sometimes there are clouds of gloom,

But these are transient all;

If the shower will make the roses bloom,

O why lament its fall?

I learnt this poem off by heart and as soon as I could read fluently, my Mum had bought me abridged versions of Jane Eyre and Wuthering Heights. She also brought me library books concerning their lives to pour over. One I continued to renew, was Brian Wilkes, The Brontës and my absolute favourite Margot Peters Unquiet Soul, both published in 1975. In the Notes section of Unquiet Soul, I was fascinated by some brief genealogical details concerning the Irish and Cornish relatives of the Brontë family. I wondered if I could perhaps find out if there were any living relatives or if, as I really hoped, I could discover that I was related to the Brontës, hence my unexplained obsession with them?

My parents encouraged my obsession and I was regularly rewarded with membership of the Brontë Society despite my relatively young age. They arranged for me to visit Haworth annually and we would stay at the Black Bull Hotel, which in those days was run by a very welcoming couple who allowed me to sit on Branwell’s chair. I even attended Society events and a kind lady took me to the AGM meeting where I sat soaking up the atmosphere, believing that I was incredibly honoured and special to be allowed to participate, even though I had no idea what they were talking about. The Parsonage also allowed me, a very precocious but shy girl of eight, into their library to do my genealogical research. I showed them what I had produced, and they were so kind in offering me additional avenues to research. Somewhere in my Dad’s loft, I think there is still a very detailed Brontë family tree.

Then Kate Bush came along. With her supposed ballet training and love of the Brontës, she was always going to be a heroine of mine. I wrote to her and was ecstatic when I received a signed poster, which remained on my bedroom wall for many years. The first album my parents bought me was The Kick Inside and I would listen to Wuthering Heights repeatedly, dancing to it like some demented banshee.

As the years passed, my love never waned. We would still make our pilgrimage and as I was older, we would always incorporate a long walk across the moors to the Brontë Falls and Top Withens. For years I kept an empty aspirin bottle on my dressing table that contained the water from the falls as though it was some magical elixir.

I’m sure that part of the reason I chose to study French literature at Hull University was because of my Brontë obsession. In fact, during my year abroad, I would regularly visit Brussels and retrace the steps of the Brontës with my worn copy of Villette; my favourite Brontë novel. I went into a Catholic Church, lit many candles and pretended to confess my sins. I even had the notion that I should fall in love with a Frenchman to truly identify with Charlotte and Lucy Snowe. Yet it never happened.

Over the years I have discovered many other cultural passions, but nothing has ever come close to my obsession with the Brontës. One of the benefits of our digital age is that I can discuss all things Brontë with other lovers via social media. There is a very supportive and welcoming group on Facebook. The Brontë Parsonage Museum is now far more involved than it ever was. There are regular events and some great opportunities such as participating in workshops led by Simon Armitage and Sally Wainwright.

My brother died unexpectedly in 2013 and he was always nagging me to do a PhD. I did start to produce my own study / book of the Brontë relic forgers TJWise and Clement Shorter. As part of my initial studies into this, I went to the Brotherton library and held an actual letter written by Charlotte Brontë. The Brotherton is an incredible Aladdin’s cave for Brontë lovers. They even have some of their collection online. I then somehow ended going down the road of fiction writing instead. I’m sure that I will go back to that one day, when work commitments allow.

Last year on my birthday, my husband arranged an incredible surprise for me. I’d always wanted a reproduction Charlotte Bronte ring from the shop. However, it is very expensive as it needs to be custom made. We went into the shop and whilst I was there, my husband called me over. Then in front of me, he produced my own Charlotte ring. I ended up in tears, as did most of the shop staff!

So, next week I’m really looking forward once again to going, as we always called it in our family, to the Brontës. I’ll go around the Parsonage at least twice, spend time, and quite a bit of money in the shop, visit the Church, walk down the cobbled Main Street and then sit just soaking up the atmosphere. I can’t always make it onto the moors now as I have a very bad back. But I’ll definitely give it a try.

Sometimes, there’s no place I would rather be.