This is a blog about the Bronte Sisters, Charlotte, Emily and Anne. And their father Patrick, their mother Maria and their brother Branwell. About their pets, their friends, the parsonage (their house), Haworth the town in which they lived, the moors they loved so much, the Victorian era in which they lived.

I've dreamt in my life dreams that have stayed with me ever after, and changed my ideas: they've gone through and through me, like wine through water, and altered the color of my mind.

Emily BronteWuthering Heights

maandag 16 december 2019

donderdag 12 december 2019

How Would The Brontës Have Voted?

It is commonly stated that the sisters were ‘high Tory’, but before Labour supporting Brontë fans go red in the face it’s important to remember that voters at this time had only two choices: Tory, equivalent to the modern day Conservatives, or Whig, who evolved into the current Liberal Democrats.

It’s also important of course to remember that large sections of the country were completely disenfranchised. Women over 21 wouldn’t be allowed the vote until 108 years after Anne was born. The vast majority of men, including Patrick and Branwell Brontë, were also barred from voting by the archaic system then in place. By 1832 around 1 in 1000 people had the vote in England. Cities that were growing rapidly such as Leeds and Manchester had no MPs at all while Dunwich, with a recorded population of 32, was represented by two Members of Parliament.

This was a source of great unrest, with the Chartist movement calling for large scale reforms, including votes for men. The area around Haworth was said to be a hotbed of Chartist activity, with the threat of a violent uprising hanging in the air. This was an inspiration for Shirley by Charlotte Brontë, as well as a reason that Patrick slept with loaded pistols by his bed every night.

It’s also important of course to remember that large sections of the country were completely disenfranchised. Women over 21 wouldn’t be allowed the vote until 108 years after Anne was born. The vast majority of men, including Patrick and Branwell Brontë, were also barred from voting by the archaic system then in place. By 1832 around 1 in 1000 people had the vote in England. Cities that were growing rapidly such as Leeds and Manchester had no MPs at all while Dunwich, with a recorded population of 32, was represented by two Members of Parliament.

This was a source of great unrest, with the Chartist movement calling for large scale reforms, including votes for men. The area around Haworth was said to be a hotbed of Chartist activity, with the threat of a violent uprising hanging in the air. This was an inspiration for Shirley by Charlotte Brontë, as well as a reason that Patrick slept with loaded pistols by his bed every night.

Do you want to read more of this interesting article: annebronte

dinsdag 3 december 2019

Winter And The Brontë Sisters

The holly tree has long been synonymous with winter and with Christmas, as the beautiful carol ‘The Holly And The Ivy’ shows. This is an old hymn and its associations are older, for holly has been revered since pagan times. It is a symbol of rebirth, for in the depths of winter it is said that the Holly King reigns over the world, to be replaced by the Oak King when new roots and new life appear.

Emily loved the Holly king’s reign, and winter was always a magical time for her. For Emily Brontë, holly also symbolised the importance of friendship, and its pre-eminence over everything else. We see this in her poem ‘Love And Friendship’, also dating from 1844, and obviously written with the love of her life in mind, her closest friends and confidante, Anne Brontë. It is a sweet poem for this sweetest of seasons – so I leave you with it now, and with Emily’s winter blessing – may your garlands always be green!

Emily loved the Holly king’s reign, and winter was always a magical time for her. For Emily Brontë, holly also symbolised the importance of friendship, and its pre-eminence over everything else. We see this in her poem ‘Love And Friendship’, also dating from 1844, and obviously written with the love of her life in mind, her closest friends and confidante, Anne Brontë. It is a sweet poem for this sweetest of seasons – so I leave you with it now, and with Emily’s winter blessing – may your garlands always be green!

Love and Friendship

By Emily Brontë

Love is like the wild rose-briar,

Friendship like the holly-tree—

The holly is dark when the rose-briar blooms

But which will bloom most constantly?

The wild rose-briar is sweet in spring,

Its summer blossoms scent the air;

Yet wait till winter comes again

And who will call the wild-briar fair?

Then scorn the silly rose-wreath now

And deck thee with the holly’s sheen,

That when December blights thy brow

He still may leave thy garland green.

Read more : annebronte

Ponden Hall.

Built in 1634, Ponden was home to the Heaton family for generations – and also an inspiration to the Bronte children, who visited here often.

Emily based parts of her novel ‘Wuthering Heights’ here; Branwell caroused at pre-hunt meets here, and wrote a short ghost story about the family; Charlotte, Branwell and Emily all used the library and ran for shelter here in the great Crow Hill Bog Burst of 1824.

ponden-hall/blogCHRISTMAS lights were switched on in Haworth and Steeton.

CHRISTMAS lights were switched on in Haworth as local villages gear up for the festive season.

The first-ever Haworth switch-on was hailed a great success by local business people who organised the family event last Saturday.

Crowds flocked to watch the official switch-on at the Christmas tree at the bottom of Main Street by BBC Look North presenter Harry Gration.

Spokesman Josie Price, who runs Weavers Guesthouse, said: “The switch-on exceeded all our expectations in terms of attendance, and feedback has been really encouraging. Harry Gration was super, a real gentleman. You could tell his fondness for Haworth, which resonated with the mainly local crowd. Look for beautiful pictures on this page keighleynews-christmas-lights

donderdag 21 november 2019

Charlotte’s LittleBook is coming home!

Breaking news! We did it: Charlotte’s #LittleBook is coming home! Massive thank you to everyone, esp National Heritage Memorial Fund, our amazing staff and most of all, YOU. We couldn’t have done it without you.

Aunt Branwell wore these wooden pattens over her shoes.

Aunt Branwell wore these wooden pattens over her shoes to keep out the creeping cold that rose from the stone floors of the parsonage. twitter/BronteParsonage

vrijdag 15 november 2019

Judi Dench appeals for help to return rare Charlotte Brontë manuscript to Britain

Containing a story which is a precursor to a famous passage in her novel Jane Eyre, it was bought for £690,850 by La Musee des Lettres et Manuscrits in Paris in 2011.

It features three short stories, one of which describes a murderer driven to madness after being haunted by his victims, and how "an immense fire" burning in his head causes his bed curtains to set alight.

The museum closed amid a financial scandal and the manuscript will be auctioned in Paris next week. The Brontë Parsonage Museum in Haworth, West Yorkshire, is bidding to buy the 20-page book and return it to the literary family’s home. The miniature publication, called Young Men's Magazine Number 2, measures just 35mm x 61mm.

The Museum believes this is "a clear precursor" of a scene between Bertha and Edward Rochester in Jane Eyre, Charlotte’s classic novel, which would be published 17 years later.

The book is expected to sell for £650,000 at next Monday’s auction. A crowdfunding appeal launched by the Museum has raised £53,000, which would be added to funds pledged from other institutions for the bid.

Dame Judi, president of the Brontë Society, said: “These tiny manuscripts are like a magical doorway into the imaginary worlds they (the sisters) inhabited and also hint at their ambition to become published authors.”

The book has been in private hands since Charlotte's death in 1855 at the age of 38.

The Museum said: “It came up for auction once before, just eight years ago, only to slip through our grasp and disappear into a private collection. It has barely been seen since.”

Charlotte carefully folded and stitched the little magazine into its brown paper cover and filled it with over 4,000 tiny written words.

It is one in a sequence of six little books, of which five are known to have survived. Four are currently housed at the Yorkshire museum.

maandag 11 november 2019

vrijdag 8 november 2019

While other inmates sat on wooden benches, Nancy had her own armchair. There was much interest in the old lady who had been the Bronte family’s nanny, and she was visited by journalists keen to interview the last person to know the famous literary sisters.

Nancy loved to talk about her time with the Brontes. But with old age, and poverty, came a fear of ending up in a pauper's grave. When Nancy told the Pall Mall Gazette it was her last request to avoid such a fate, the London newspaper appealed for public donations so she could have a decent burial. It was taken up by other newspapers, including the New York Times. How much was raised isn’t clear. A 'typo' in a Manchester newspaper meant that some of the money was sent to Bedford workhouse, instead of Bradford...

And when Nancy died in 1886, aged 82, she was buried at Undercliffe Cemetery, in an unmarked grave costing just a guinea. For over 130 years she has laid in the weed-choked plot. Now she has been added to a list of ‘Bradford Worthies’ buried at the cemetery, and finally she is to have a headstone. “Nancy has been hidden all these years. We want to acknowledge her part in Bronte history,” says Allan Hillary, chairman of the Friends of Undercliffe Cemetery which is appealing for help to raise £3,000 for a headstone and to clear the area around the grave. Allan hopes it will become part of the Bronte Trail, attracting more visitors to the historic cemetery.

Stephen Lightfoot came across Nancy in newspaper archives. He and other cemetery volunteers spent six months researching her and, after finding her plot in burial records, cleared the waist-high overgrowth from it. “Nancy was a faithful servant of the Brontes for eight years and had a significant impact on the children,” says Stephen. “As well as the daily routine of looking after them, she took them for moorland walks and was involved in their play and early stories. The rich and famous are always remembered, but Nancy is representative of ordinary working people not always recognised.”

One of 12 children of a Bradford shoemaker, Nancy is remembered for another reason too - she restored Patrick Bronte’s reputation at a time when history was re-written.

Nancy was at industrial school, learning housekeeping and childcare, when, aged 13, she was employed by Patrick as a nurse to his baby daughter, Charlotte, in 1816. When Nancy’s sister, Sarah, was later taken on too Nancy was promoted to cook and assistant housekeeper. The sisters lived with the Brontes at Thornton, moving with them to Haworth in 1820. “They must have been quite a sight - trudging up Haworth main street in a carriage, with half a dozen carts behind. Little did the onlookers know this family would make Haworth world famous,” says Stephen.

When the Brontes’ mother, Maria, died in 1821 her sister looked after the household, and Nancy and Sarah were no longer needed. But, says Stephen, Patrick thought so highly of them he gave them a substantial £10 each as a leaving present. In 1824 Nancy married John Wainwright and they had a daughter, Emily. John died in 1838 and Nancy later married Irishman John Malone, who worked at a wool warehouse in Cheapside, Bradford.

By 1857, when Elizabeth Gaskell’s biography The Life of Charlotte Bronte was published, Nancy had outlived the Bronte siblings. “Mrs Gaskell’s book made outlandish claims about Patrick; among them that he burned the children’s boots, cut up Maria’s dresses and fired pistols out of the Parsonage door. She also called Nancy and Sarah ‘wasteful servants’,” says Stephen. “Nancy was angry and went to see Patrick, who wrote a reference for the sisters, stating: ‘I can truly say that no master was ever blessed with two more careful and honest servants’. Nancy had it framed.”

Adds Stephen: “It seems Mrs Gaskell got her evidence from a village woman who’d been fired by Patrick. After meeting Nancy, Patrick’s friend, William Dearden, wrote a letter to the Bradford Observer defending him. Mrs Gaskell withdrew some statements. Nancy played a major part in restoring his reputation.”

When Nancy’s second husband died she fell into poverty and in 1884, aged 80 she left her Manningham home for the workhouse. It was then that Nancy parted company with treasured gifts from Patrick and his children, known as the ‘Bronte relics’

They included a roasting jack from the Parsonage, a little book from Charlotte to Nancy’s child, and what is thought to be a photograph of Charlotte on glass, which she showed to a local journalist.

“Nancy never tired of talking about her days with the Brontes and when she was offered £5 for a letter from Charlotte she wouldn’t part with it,” says Stephen.

So why did her Bronte relics end up with her nephew, John Hodgson Widdop, a Manchester Road draper. Did Nancy ask him to look after them? Did she sell them to him? Stephen’s research revealed that Widdop was bankrupt and served time in prison for obtaining goods by false pretences. A Bradford Daily Telegraph report in 1885 lists a “collection of Bronte curiosities” Widdop displayed at a bazaar in the city. He later sold three Bronte relics, including Patrick’s 1857 letter, to the Parsonage Museum.

The Charlotte photograph remains a mystery. Says Stephen: “Did it survive? Will it ever be discovered? It may have been an Ambrotype photograph ‘taken on glass’ after 1852. Or a Dagurreotype taken earlier.”

It was Widdop who dealt with the funds raised for Nancy’s burial. She was buried with his mother, (Nancy’s sister, Mary), and father - there was no headstone, but the Bradford Daily Telegraph reported that she arrived at the cemetery by hearse in a “black coffin with brass furnishings and two wreaths of flowers”.

Nancy’s obituary in the Keighley News on April 3, 1886 said: “All her means were gone and she accepted the workhouse as an asylum wherein to spend the remainder of her days.” Stephen is researching the whereabouts of Nancy’s daughter, Emily.

Victorian hierarchy continued in death at Undercliffe Cemetery. There are 124,000 burials there, in plots ranging from ornate headstones to paupers’ graves - one containing 124 people. Now Nancy is one of the “Bradford Worthies” whose stories, researched by volunteers, are told in the cemetery. By scanning their phones on a series of QR codes around the site, visitors can learn more about people buried there.

“As well as civic and industrial leaders we remember people like Nancy who did good things but, as ordinary working people, were erased from history," says Stephen.

Adds Allan: "Like many interesting characters buried here, Nancy was hidden in undergrowth for a long time. We have an important part of the Bronte story right here."

Nancy's story will be included in a "Bradford Worthies" tour at Undercliffe Cemetery in September. Also that month, Bradford actress and writer Irene Lofthouse will be talking about Nancy's life in character. (Read more)

Abonneren op:

Posts (Atom)

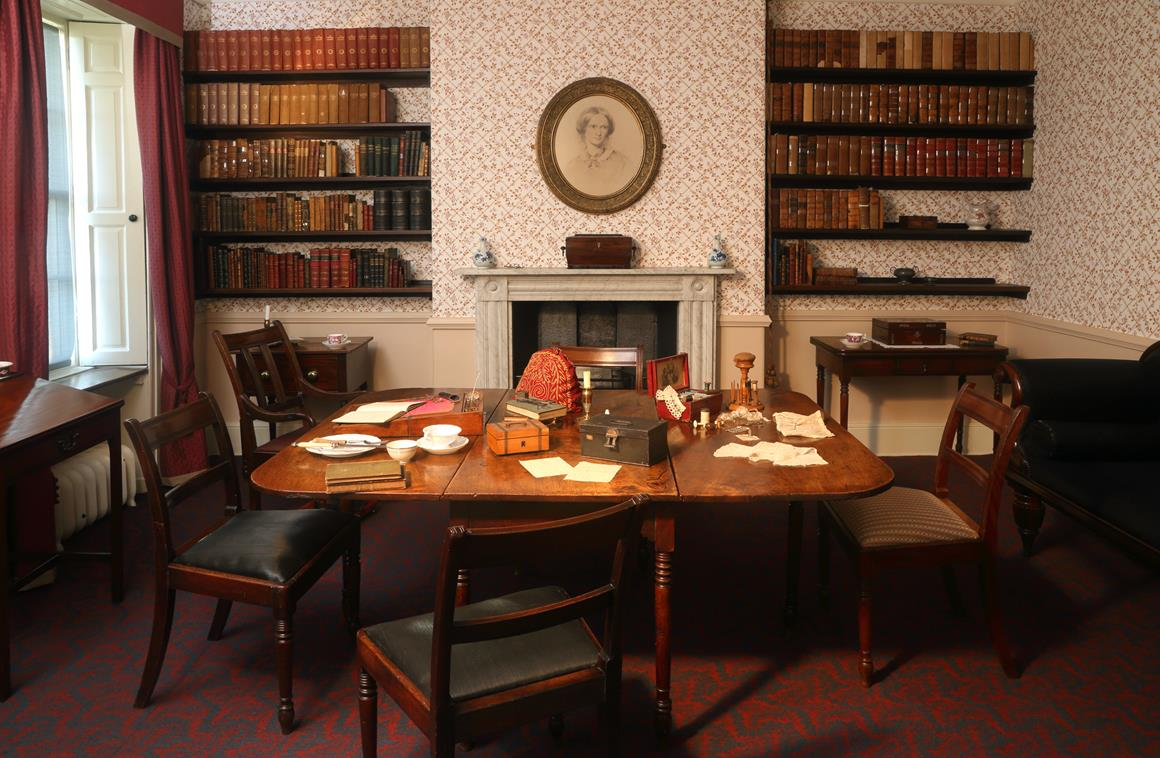

The Parlour

Parsonage

Charlotte Bronte

Presently the door opened, and in came a superannuated mastiff, followed by an old gentleman very like Miss Bronte, who shook hands with us, and then went to call his daughter. A long interval, during which we coaxed the old dog, and looked at a picture of Miss Bronte, by Richmond, the solitary ornament of the room, looking strangely out of place on the bare walls, and at the books on the little shelves, most of them evidently the gift of the authors since Miss Bronte's celebrity. Presently she came in, and welcomed us very kindly, and took me upstairs to take off my bonnet, and herself brought me water and towels. The uncarpeted stone stairs and floors, the old drawers propped on wood, were all scrupulously clean and neat. When we went into the parlour again, we began talking very comfortably, when the door opened and Mr. Bronte looked in; seeing his daughter there, I suppose he thought it was all right, and he retreated to his study on the opposite side of the passage; presently emerging again to bring W---- a country newspaper. This was his last appearance till we went. Miss Bronte spoke with the greatest warmth of Miss Martineau, and of the good she had gained from her. Well! we talked about various things; the character of the people, - about her solitude, etc., till she left the room to help about dinner, I suppose, for she did not return for an age. The old dog had vanished; a fat curly-haired dog honoured us with his company for some time, but finally manifested a wish to get out, so we were left alone. At last she returned, followed by the maid and dinner, which made us all more comfortable; and we had some very pleasant conversation, in the midst of which time passed quicker than we supposed, for at last W---- found that it was half-past three, and we had fourteen or fifteen miles before us. So we hurried off, having obtained from her a promise to pay us a visit in the spring... ------------------- "She cannot see well, and does little beside knitting. The way she weakened her eyesight was this: When she was sixteen or seventeen, she wanted much to draw; and she copied nimini-pimini copper-plate engravings out of annuals, ('stippling,' don't the artists call it?) every little point put in, till at the end of six months she had produced an exquisitely faithful copy of the engraving. She wanted to learn to express her ideas by drawing. After she had tried to draw stories, and not succeeded, she took the better mode of writing; but in so small a hand, that it is almost impossible to decipher what she wrote at this time.

I asked her whether she had ever taken opium, as the description given of its effects in Villette was so exactly like what I had experienced, - vivid and exaggerated presence of objects, of which the outlines were indistinct, or lost in golden mist, etc. She replied, that she had never, to her knowledge, taken a grain of it in any shape, but that she had followed the process she always adopted when she had to describe anything which had not fallen within her own experience; she had thought intently on it for many and many a night before falling to sleep, - wondering what it was like, or how it would be, - till at length, sometimes after the progress of her story had been arrested at this one point for weeks, she wakened up in the morning with all clear before her, as if she had in reality gone through the experience, and then could describe it, word for word, as it had happened. I cannot account for this psychologically; I only am sure that it was so, because she said it. ----------------------She thought much of her duty, and had loftier and clearer notions of it than most people, and held fast to them with more success. It was done, it seems to me, with much more difficulty than people have of stronger nerves, and better fortunes. All her life was but labour and pain; and she never threw down the burden for the sake of present pleasure. I don't know what use you can make of all I have said. I have written it with the strong desire to obtain appreciation for her. Yet, what does it matter? She herself appealed to the world's judgement for her use of some of the faculties she had, - not the best, - but still the only ones she could turn to strangers' benefit. They heartily, greedily enjoyed the fruits of her labours, and then found out she was much to be blamed for possessing such faculties. Why ask for a judgement on her from such a world?" elizabeth gaskell/charlotte bronte

I asked her whether she had ever taken opium, as the description given of its effects in Villette was so exactly like what I had experienced, - vivid and exaggerated presence of objects, of which the outlines were indistinct, or lost in golden mist, etc. She replied, that she had never, to her knowledge, taken a grain of it in any shape, but that she had followed the process she always adopted when she had to describe anything which had not fallen within her own experience; she had thought intently on it for many and many a night before falling to sleep, - wondering what it was like, or how it would be, - till at length, sometimes after the progress of her story had been arrested at this one point for weeks, she wakened up in the morning with all clear before her, as if she had in reality gone through the experience, and then could describe it, word for word, as it had happened. I cannot account for this psychologically; I only am sure that it was so, because she said it. ----------------------She thought much of her duty, and had loftier and clearer notions of it than most people, and held fast to them with more success. It was done, it seems to me, with much more difficulty than people have of stronger nerves, and better fortunes. All her life was but labour and pain; and she never threw down the burden for the sake of present pleasure. I don't know what use you can make of all I have said. I have written it with the strong desire to obtain appreciation for her. Yet, what does it matter? She herself appealed to the world's judgement for her use of some of the faculties she had, - not the best, - but still the only ones she could turn to strangers' benefit. They heartily, greedily enjoyed the fruits of her labours, and then found out she was much to be blamed for possessing such faculties. Why ask for a judgement on her from such a world?" elizabeth gaskell/charlotte bronte

Poem: No coward soul is mine

No coward soul is mine,

No trembler in the worlds storm-troubled sphere:

I see Heavens glories shine,

And faith shines equal, arming me from fear.

O God within my breast.

Almighty, ever-present Deity!

Life -- that in me has rest,

As I -- Undying Life -- have power in Thee!

Vain are the thousand creeds

That move mens hearts: unutterably vain;

Worthless as withered weeds,

Or idlest froth amid the boundless main,

To waken doubt in one

Holding so fast by Thine infinity;

So surely anchored on

The steadfast Rock of immortality.

With wide-embracing love

Thy Spirit animates eternal years,

Pervades and broods above,

Changes, sustains, dissolves, creates, and rears.

Though earth and man were gone,

And suns and universes ceased to be,

And Thou wert left alone,

Every existence would exist in Thee.

There is not room for Death,

Nor atom that his might could render void:

Thou -- Thou art Being and Breath,

And what Thou art may never be destroyed.

-- Emily Bronte

No trembler in the worlds storm-troubled sphere:

I see Heavens glories shine,

And faith shines equal, arming me from fear.

O God within my breast.

Almighty, ever-present Deity!

Life -- that in me has rest,

As I -- Undying Life -- have power in Thee!

Vain are the thousand creeds

That move mens hearts: unutterably vain;

Worthless as withered weeds,

Or idlest froth amid the boundless main,

To waken doubt in one

Holding so fast by Thine infinity;

So surely anchored on

The steadfast Rock of immortality.

With wide-embracing love

Thy Spirit animates eternal years,

Pervades and broods above,

Changes, sustains, dissolves, creates, and rears.

Though earth and man were gone,

And suns and universes ceased to be,

And Thou wert left alone,

Every existence would exist in Thee.

There is not room for Death,

Nor atom that his might could render void:

Thou -- Thou art Being and Breath,

And what Thou art may never be destroyed.

-- Emily Bronte

Family tree

The Bronte Family

Grandparents - paternal

Hugh Brunty was born 1755 and died circa 1808. He married Eleanor McClory, known as Alice in 1776.

Grandparents - maternal

Thomas Branwell (born 1746 died 5th April 1808) was married in 1768 to Anne Carne (baptised 27th April 1744 and died 19th December 1809).

Parents

Father was Patrick Bronte, the eldest of 10 children born to Hugh Brunty and Eleanor (Alice) McClory. He was born 17th March 1777 and died on 7th June 1861. Mother was Maria Branwell, who was born on 15th April 1783 and died on 15th September 1821.

Maria had a sister, Elizabeth who was known as Aunt Branwell. She was born in 1776 and died on 29th October 1842.

Patrick Bronte married Maria Branwell on 29th December 1812.

The Bronte Children

Patrick and Maria Bronte had six children.

The first child was Maria, who was born in 1814 and died on 6th June 1825.

The second daughter, Elizabeth was born on 8th February 1815 and died shortly after Maria on 15th June 1825. Charlotte was the third daughter, born on 21st April 1816.

Charlotte married Arthur Bell Nicholls (born 1818) on 29th June 1854. Charlotte died on 31st March 1855. Arthur lived until 2nd December 1906.

The first and only son born to Patrick and Maria was Patrick Branwell, who was born on 26th June 1817 and died on 24th September 1848.

Emily Jane, the fourth daughter was born on 30th July 1818 and died on 19th December 1848.

The sixth and last child was Anne, born on 17th January 1820 who died on 28th May 1849.

Grandparents - paternal

Hugh Brunty was born 1755 and died circa 1808. He married Eleanor McClory, known as Alice in 1776.

Grandparents - maternal

Thomas Branwell (born 1746 died 5th April 1808) was married in 1768 to Anne Carne (baptised 27th April 1744 and died 19th December 1809).

Parents

Father was Patrick Bronte, the eldest of 10 children born to Hugh Brunty and Eleanor (Alice) McClory. He was born 17th March 1777 and died on 7th June 1861. Mother was Maria Branwell, who was born on 15th April 1783 and died on 15th September 1821.

Maria had a sister, Elizabeth who was known as Aunt Branwell. She was born in 1776 and died on 29th October 1842.

Patrick Bronte married Maria Branwell on 29th December 1812.

The Bronte Children

Patrick and Maria Bronte had six children.

The first child was Maria, who was born in 1814 and died on 6th June 1825.

The second daughter, Elizabeth was born on 8th February 1815 and died shortly after Maria on 15th June 1825. Charlotte was the third daughter, born on 21st April 1816.

Charlotte married Arthur Bell Nicholls (born 1818) on 29th June 1854. Charlotte died on 31st March 1855. Arthur lived until 2nd December 1906.

The first and only son born to Patrick and Maria was Patrick Branwell, who was born on 26th June 1817 and died on 24th September 1848.

Emily Jane, the fourth daughter was born on 30th July 1818 and died on 19th December 1848.

The sixth and last child was Anne, born on 17th January 1820 who died on 28th May 1849.

Top Withens in the snow.

Blogarchief

-

►

2024

(10)

- ► 03/17 - 03/24 (1)

- ► 02/18 - 02/25 (1)

- ► 01/21 - 01/28 (5)

- ► 01/14 - 01/21 (1)

- ► 01/07 - 01/14 (2)

-

►

2023

(9)

- ► 11/26 - 12/03 (1)

- ► 11/19 - 11/26 (1)

- ► 07/23 - 07/30 (1)

- ► 05/28 - 06/04 (1)

- ► 05/14 - 05/21 (1)

- ► 05/07 - 05/14 (1)

- ► 04/02 - 04/09 (1)

- ► 03/05 - 03/12 (1)

- ► 02/05 - 02/12 (1)

-

►

2022

(27)

- ► 12/25 - 01/01 (1)

- ► 12/04 - 12/11 (1)

- ► 11/20 - 11/27 (1)

- ► 11/13 - 11/20 (2)

- ► 10/30 - 11/06 (2)

- ► 10/23 - 10/30 (2)

- ► 10/09 - 10/16 (2)

- ► 07/17 - 07/24 (1)

- ► 06/12 - 06/19 (1)

- ► 06/05 - 06/12 (1)

- ► 05/22 - 05/29 (2)

- ► 02/27 - 03/06 (1)

- ► 02/20 - 02/27 (1)

- ► 02/13 - 02/20 (7)

- ► 01/16 - 01/23 (2)

-

►

2021

(47)

- ► 12/19 - 12/26 (1)

- ► 12/12 - 12/19 (1)

- ► 11/28 - 12/05 (1)

- ► 11/21 - 11/28 (2)

- ► 11/14 - 11/21 (1)

- ► 10/31 - 11/07 (2)

- ► 08/15 - 08/22 (1)

- ► 08/08 - 08/15 (1)

- ► 08/01 - 08/08 (1)

- ► 07/25 - 08/01 (1)

- ► 07/18 - 07/25 (1)

- ► 07/11 - 07/18 (1)

- ► 06/20 - 06/27 (3)

- ► 06/13 - 06/20 (2)

- ► 06/06 - 06/13 (3)

- ► 05/30 - 06/06 (7)

- ► 05/23 - 05/30 (8)

- ► 05/02 - 05/09 (2)

- ► 04/18 - 04/25 (4)

- ► 04/11 - 04/18 (1)

- ► 03/28 - 04/04 (2)

- ► 01/03 - 01/10 (1)

-

►

2020

(34)

- ► 12/20 - 12/27 (1)

- ► 12/06 - 12/13 (5)

- ► 11/08 - 11/15 (2)

- ► 11/01 - 11/08 (1)

- ► 10/11 - 10/18 (1)

- ► 10/04 - 10/11 (1)

- ► 09/06 - 09/13 (4)

- ► 08/16 - 08/23 (3)

- ► 08/02 - 08/09 (2)

- ► 07/12 - 07/19 (1)

- ► 07/05 - 07/12 (1)

- ► 06/28 - 07/05 (1)

- ► 04/19 - 04/26 (1)

- ► 03/22 - 03/29 (1)

- ► 02/09 - 02/16 (2)

- ► 01/26 - 02/02 (2)

- ► 01/12 - 01/19 (3)

- ► 01/05 - 01/12 (2)

-

▼

2019

(34)

- ► 12/29 - 01/05 (2)

- ► 12/01 - 12/08 (3)

- ► 11/17 - 11/24 (2)

- ► 11/10 - 11/17 (2)

- ► 10/13 - 10/20 (2)

- ► 10/06 - 10/13 (1)

- ► 09/22 - 09/29 (1)

- ► 09/08 - 09/15 (1)

- ► 09/01 - 09/08 (3)

- ► 08/25 - 09/01 (2)

- ► 07/21 - 07/28 (1)

- ► 06/30 - 07/07 (2)

- ► 06/09 - 06/16 (1)

- ► 05/26 - 06/02 (1)

- ► 04/14 - 04/21 (1)

- ► 04/07 - 04/14 (1)

- ► 03/03 - 03/10 (1)

- ► 02/17 - 02/24 (2)

- ► 02/10 - 02/17 (1)

- ► 02/03 - 02/10 (1)

-

►

2018

(82)

- ► 12/30 - 01/06 (2)

- ► 12/23 - 12/30 (4)

- ► 12/16 - 12/23 (2)

- ► 11/25 - 12/02 (1)

- ► 11/18 - 11/25 (2)

- ► 11/11 - 11/18 (3)

- ► 11/04 - 11/11 (1)

- ► 10/28 - 11/04 (3)

- ► 10/21 - 10/28 (3)

- ► 10/07 - 10/14 (4)

- ► 09/23 - 09/30 (1)

- ► 08/26 - 09/02 (1)

- ► 08/19 - 08/26 (1)

- ► 08/05 - 08/12 (1)

- ► 07/29 - 08/05 (8)

- ► 07/22 - 07/29 (6)

- ► 06/24 - 07/01 (2)

- ► 06/17 - 06/24 (2)

- ► 06/10 - 06/17 (4)

- ► 06/03 - 06/10 (5)

- ► 05/27 - 06/03 (3)

- ► 05/20 - 05/27 (1)

- ► 05/13 - 05/20 (1)

- ► 05/06 - 05/13 (1)

- ► 04/29 - 05/06 (1)

- ► 04/22 - 04/29 (1)

- ► 04/15 - 04/22 (1)

- ► 04/08 - 04/15 (2)

- ► 04/01 - 04/08 (1)

- ► 03/25 - 04/01 (1)

- ► 03/18 - 03/25 (3)

- ► 03/11 - 03/18 (2)

- ► 03/04 - 03/11 (2)

- ► 02/11 - 02/18 (2)

- ► 01/14 - 01/21 (4)

-

►

2017

(69)

- ► 12/31 - 01/07 (2)

- ► 12/24 - 12/31 (1)

- ► 12/17 - 12/24 (1)

- ► 12/10 - 12/17 (2)

- ► 12/03 - 12/10 (4)

- ► 11/26 - 12/03 (1)

- ► 11/19 - 11/26 (5)

- ► 11/12 - 11/19 (2)

- ► 10/08 - 10/15 (2)

- ► 10/01 - 10/08 (2)

- ► 09/10 - 09/17 (2)

- ► 08/27 - 09/03 (2)

- ► 07/30 - 08/06 (1)

- ► 07/23 - 07/30 (1)

- ► 07/16 - 07/23 (3)

- ► 07/09 - 07/16 (1)

- ► 06/25 - 07/02 (3)

- ► 06/04 - 06/11 (1)

- ► 05/28 - 06/04 (1)

- ► 05/07 - 05/14 (2)

- ► 04/30 - 05/07 (2)

- ► 04/23 - 04/30 (1)

- ► 04/16 - 04/23 (2)

- ► 04/09 - 04/16 (2)

- ► 04/02 - 04/09 (3)

- ► 03/26 - 04/02 (1)

- ► 03/19 - 03/26 (1)

- ► 03/05 - 03/12 (4)

- ► 02/12 - 02/19 (1)

- ► 02/05 - 02/12 (4)

- ► 01/29 - 02/05 (1)

- ► 01/22 - 01/29 (2)

- ► 01/15 - 01/22 (2)

- ► 01/08 - 01/15 (2)

- ► 01/01 - 01/08 (2)

-

►

2016

(126)

- ► 12/25 - 01/01 (3)

- ► 12/18 - 12/25 (4)

- ► 12/04 - 12/11 (1)

- ► 11/27 - 12/04 (4)

- ► 11/20 - 11/27 (1)

- ► 11/13 - 11/20 (3)

- ► 11/06 - 11/13 (8)

- ► 10/30 - 11/06 (1)

- ► 10/23 - 10/30 (1)

- ► 10/16 - 10/23 (3)

- ► 10/09 - 10/16 (2)

- ► 10/02 - 10/09 (3)

- ► 09/11 - 09/18 (1)

- ► 08/28 - 09/04 (2)

- ► 08/21 - 08/28 (3)

- ► 08/07 - 08/14 (1)

- ► 07/31 - 08/07 (1)

- ► 07/24 - 07/31 (4)

- ► 07/17 - 07/24 (3)

- ► 07/03 - 07/10 (1)

- ► 06/26 - 07/03 (4)

- ► 06/19 - 06/26 (3)

- ► 06/12 - 06/19 (2)

- ► 06/05 - 06/12 (8)

- ► 05/29 - 06/05 (3)

- ► 05/22 - 05/29 (3)

- ► 05/08 - 05/15 (3)

- ► 05/01 - 05/08 (2)

- ► 04/24 - 05/01 (1)

- ► 04/17 - 04/24 (6)

- ► 04/10 - 04/17 (2)

- ► 04/03 - 04/10 (1)

- ► 03/27 - 04/03 (6)

- ► 03/20 - 03/27 (4)

- ► 03/13 - 03/20 (7)

- ► 03/06 - 03/13 (6)

- ► 02/28 - 03/06 (3)

- ► 02/21 - 02/28 (1)

- ► 02/14 - 02/21 (2)

- ► 02/07 - 02/14 (2)

- ► 01/31 - 02/07 (2)

- ► 01/17 - 01/24 (2)

- ► 01/10 - 01/17 (1)

- ► 01/03 - 01/10 (2)

-

►

2015

(192)

- ► 12/27 - 01/03 (4)

- ► 12/20 - 12/27 (4)

- ► 12/13 - 12/20 (6)

- ► 12/06 - 12/13 (3)

- ► 11/29 - 12/06 (1)

- ► 11/22 - 11/29 (4)

- ► 11/15 - 11/22 (4)

- ► 11/08 - 11/15 (8)

- ► 11/01 - 11/08 (2)

- ► 10/25 - 11/01 (4)

- ► 10/18 - 10/25 (2)

- ► 10/11 - 10/18 (2)

- ► 10/04 - 10/11 (2)

- ► 09/27 - 10/04 (4)

- ► 09/20 - 09/27 (3)

- ► 09/13 - 09/20 (2)

- ► 09/06 - 09/13 (2)

- ► 08/30 - 09/06 (3)

- ► 08/23 - 08/30 (1)

- ► 08/16 - 08/23 (4)

- ► 08/09 - 08/16 (2)

- ► 08/02 - 08/09 (4)

- ► 07/26 - 08/02 (5)

- ► 07/19 - 07/26 (2)

- ► 07/12 - 07/19 (3)

- ► 07/05 - 07/12 (1)

- ► 06/21 - 06/28 (1)

- ► 06/14 - 06/21 (10)

- ► 06/07 - 06/14 (2)

- ► 05/31 - 06/07 (6)

- ► 05/24 - 05/31 (4)

- ► 05/17 - 05/24 (2)

- ► 05/10 - 05/17 (2)

- ► 05/03 - 05/10 (4)

- ► 04/26 - 05/03 (5)

- ► 04/19 - 04/26 (7)

- ► 04/12 - 04/19 (3)

- ► 04/05 - 04/12 (3)

- ► 03/29 - 04/05 (4)

- ► 03/22 - 03/29 (4)

- ► 03/15 - 03/22 (1)

- ► 03/08 - 03/15 (8)

- ► 03/01 - 03/08 (6)

- ► 02/22 - 03/01 (6)

- ► 02/15 - 02/22 (1)

- ► 02/08 - 02/15 (3)

- ► 02/01 - 02/08 (3)

- ► 01/25 - 02/01 (8)

- ► 01/18 - 01/25 (7)

- ► 01/11 - 01/18 (7)

- ► 01/04 - 01/11 (3)

-

►

2014

(270)

- ► 12/28 - 01/04 (5)

- ► 12/21 - 12/28 (6)

- ► 12/14 - 12/21 (9)

- ► 12/07 - 12/14 (11)

- ► 11/30 - 12/07 (4)

- ► 11/23 - 11/30 (9)

- ► 11/16 - 11/23 (10)

- ► 11/09 - 11/16 (5)

- ► 11/02 - 11/09 (3)

- ► 10/26 - 11/02 (3)

- ► 10/19 - 10/26 (4)

- ► 10/12 - 10/19 (6)

- ► 10/05 - 10/12 (6)

- ► 09/28 - 10/05 (4)

- ► 09/21 - 09/28 (5)

- ► 09/07 - 09/14 (3)

- ► 08/31 - 09/07 (8)

- ► 08/24 - 08/31 (3)

- ► 08/17 - 08/24 (3)

- ► 08/10 - 08/17 (6)

- ► 08/03 - 08/10 (4)

- ► 07/27 - 08/03 (1)

- ► 07/20 - 07/27 (2)

- ► 07/13 - 07/20 (1)

- ► 07/06 - 07/13 (8)

- ► 06/29 - 07/06 (4)

- ► 06/22 - 06/29 (6)

- ► 06/15 - 06/22 (2)

- ► 06/08 - 06/15 (4)

- ► 06/01 - 06/08 (7)

- ► 05/25 - 06/01 (5)

- ► 05/18 - 05/25 (6)

- ► 05/11 - 05/18 (7)

- ► 05/04 - 05/11 (7)

- ► 04/27 - 05/04 (9)

- ► 04/20 - 04/27 (3)

- ► 04/13 - 04/20 (4)

- ► 04/06 - 04/13 (7)

- ► 03/30 - 04/06 (2)

- ► 03/23 - 03/30 (8)

- ► 03/16 - 03/23 (6)

- ► 03/09 - 03/16 (8)

- ► 03/02 - 03/09 (4)

- ► 02/23 - 03/02 (5)

- ► 02/16 - 02/23 (4)

- ► 02/09 - 02/16 (3)

- ► 02/02 - 02/09 (8)

- ► 01/26 - 02/02 (11)

- ► 01/19 - 01/26 (2)

- ► 01/12 - 01/19 (6)

- ► 01/05 - 01/12 (3)

-

►

2013

(278)

- ► 12/29 - 01/05 (7)

- ► 12/22 - 12/29 (2)

- ► 12/15 - 12/22 (9)

- ► 12/08 - 12/15 (10)

- ► 12/01 - 12/08 (3)

- ► 11/24 - 12/01 (10)

- ► 11/17 - 11/24 (7)

- ► 11/10 - 11/17 (3)

- ► 11/03 - 11/10 (5)

- ► 10/27 - 11/03 (5)

- ► 10/20 - 10/27 (3)

- ► 10/13 - 10/20 (6)

- ► 10/06 - 10/13 (6)

- ► 09/29 - 10/06 (5)

- ► 09/22 - 09/29 (6)

- ► 09/15 - 09/22 (1)

- ► 09/08 - 09/15 (4)

- ► 09/01 - 09/08 (7)

- ► 08/25 - 09/01 (9)

- ► 08/18 - 08/25 (4)

- ► 08/11 - 08/18 (6)

- ► 08/04 - 08/11 (3)

- ► 07/28 - 08/04 (8)

- ► 07/21 - 07/28 (5)

- ► 07/14 - 07/21 (3)

- ► 07/07 - 07/14 (8)

- ► 06/30 - 07/07 (8)

- ► 06/23 - 06/30 (2)

- ► 06/16 - 06/23 (7)

- ► 06/09 - 06/16 (6)

- ► 06/02 - 06/09 (3)

- ► 05/26 - 06/02 (5)

- ► 05/19 - 05/26 (3)

- ► 05/12 - 05/19 (5)

- ► 05/05 - 05/12 (4)

- ► 04/28 - 05/05 (6)

- ► 04/21 - 04/28 (5)

- ► 04/14 - 04/21 (7)

- ► 04/07 - 04/14 (7)

- ► 03/31 - 04/07 (3)

- ► 03/17 - 03/24 (1)

- ► 03/10 - 03/17 (7)

- ► 03/03 - 03/10 (5)

- ► 02/24 - 03/03 (5)

- ► 02/17 - 02/24 (6)

- ► 02/10 - 02/17 (11)

- ► 02/03 - 02/10 (12)

- ► 01/27 - 02/03 (4)

- ► 01/20 - 01/27 (5)

- ► 01/13 - 01/20 (3)

- ► 01/06 - 01/13 (3)

-

►

2012

(303)

- ► 12/30 - 01/06 (2)

- ► 12/23 - 12/30 (3)

- ► 12/16 - 12/23 (6)

- ► 12/09 - 12/16 (2)

- ► 12/02 - 12/09 (17)

- ► 11/25 - 12/02 (2)

- ► 11/18 - 11/25 (3)

- ► 11/11 - 11/18 (9)

- ► 11/04 - 11/11 (5)

- ► 10/28 - 11/04 (6)

- ► 10/21 - 10/28 (9)

- ► 10/14 - 10/21 (7)

- ► 10/07 - 10/14 (9)

- ► 09/30 - 10/07 (6)

- ► 09/23 - 09/30 (6)

- ► 09/16 - 09/23 (8)

- ► 09/09 - 09/16 (4)

- ► 09/02 - 09/09 (7)

- ► 08/26 - 09/02 (2)

- ► 08/19 - 08/26 (3)

- ► 08/05 - 08/12 (2)

- ► 07/29 - 08/05 (5)

- ► 07/22 - 07/29 (3)

- ► 07/15 - 07/22 (7)

- ► 07/08 - 07/15 (6)

- ► 07/01 - 07/08 (3)

- ► 06/24 - 07/01 (6)

- ► 06/17 - 06/24 (7)

- ► 06/10 - 06/17 (5)

- ► 06/03 - 06/10 (4)

- ► 05/27 - 06/03 (6)

- ► 05/20 - 05/27 (3)

- ► 05/13 - 05/20 (3)

- ► 05/06 - 05/13 (3)

- ► 04/29 - 05/06 (3)

- ► 04/22 - 04/29 (4)

- ► 04/15 - 04/22 (4)

- ► 04/08 - 04/15 (9)

- ► 04/01 - 04/08 (9)

- ► 03/25 - 04/01 (4)

- ► 03/18 - 03/25 (7)

- ► 03/11 - 03/18 (4)

- ► 03/04 - 03/11 (5)

- ► 02/26 - 03/04 (7)

- ► 02/19 - 02/26 (7)

- ► 02/12 - 02/19 (3)

- ► 02/05 - 02/12 (7)

- ► 01/29 - 02/05 (12)

- ► 01/22 - 01/29 (8)

- ► 01/15 - 01/22 (13)

- ► 01/08 - 01/15 (8)

- ► 01/01 - 01/08 (10)

-

►

2011

(446)

- ► 12/25 - 01/01 (12)

- ► 12/18 - 12/25 (12)

- ► 12/11 - 12/18 (14)

- ► 12/04 - 12/11 (11)

- ► 11/27 - 12/04 (13)

- ► 11/20 - 11/27 (17)

- ► 11/13 - 11/20 (19)

- ► 11/06 - 11/13 (12)

- ► 10/30 - 11/06 (10)

- ► 10/23 - 10/30 (22)

- ► 10/16 - 10/23 (5)

- ► 10/09 - 10/16 (7)

- ► 10/02 - 10/09 (8)

- ► 09/25 - 10/02 (7)

- ► 09/18 - 09/25 (9)

- ► 09/11 - 09/18 (5)

- ► 09/04 - 09/11 (4)

- ► 08/28 - 09/04 (7)

- ► 08/21 - 08/28 (8)

- ► 08/14 - 08/21 (8)

- ► 08/07 - 08/14 (8)

- ► 07/31 - 08/07 (11)

- ► 07/24 - 07/31 (7)

- ► 07/17 - 07/24 (8)

- ► 07/10 - 07/17 (9)

- ► 07/03 - 07/10 (12)

- ► 06/26 - 07/03 (9)

- ► 06/19 - 06/26 (14)

- ► 06/12 - 06/19 (11)

- ► 06/05 - 06/12 (10)

- ► 05/29 - 06/05 (10)

- ► 05/22 - 05/29 (10)

- ► 05/15 - 05/22 (11)

- ► 05/08 - 05/15 (3)

- ► 05/01 - 05/08 (8)

- ► 04/24 - 05/01 (4)

- ► 04/17 - 04/24 (5)

- ► 04/10 - 04/17 (5)

- ► 04/03 - 04/10 (9)

- ► 03/27 - 04/03 (2)

- ► 03/20 - 03/27 (3)

- ► 03/13 - 03/20 (4)

- ► 03/06 - 03/13 (11)

- ► 02/27 - 03/06 (7)

- ► 02/20 - 02/27 (10)

- ► 02/13 - 02/20 (6)

- ► 01/30 - 02/06 (1)

- ► 01/23 - 01/30 (8)

- ► 01/16 - 01/23 (4)

- ► 01/09 - 01/16 (3)

- ► 01/02 - 01/09 (13)

-

►

2010

(196)

- ► 12/26 - 01/02 (6)

- ► 12/19 - 12/26 (7)

- ► 12/12 - 12/19 (7)

- ► 12/05 - 12/12 (14)

- ► 11/28 - 12/05 (3)

- ► 11/21 - 11/28 (6)

- ► 11/14 - 11/21 (8)

- ► 11/07 - 11/14 (3)

- ► 10/31 - 11/07 (4)

- ► 10/17 - 10/24 (2)

- ► 10/10 - 10/17 (3)

- ► 10/03 - 10/10 (3)

- ► 09/26 - 10/03 (1)

- ► 09/19 - 09/26 (4)

- ► 09/12 - 09/19 (2)

- ► 09/05 - 09/12 (8)

- ► 08/29 - 09/05 (2)

- ► 08/22 - 08/29 (4)

- ► 08/15 - 08/22 (8)

- ► 08/08 - 08/15 (2)

- ► 08/01 - 08/08 (1)

- ► 07/25 - 08/01 (8)

- ► 07/18 - 07/25 (5)

- ► 07/11 - 07/18 (10)

- ► 07/04 - 07/11 (4)

- ► 06/27 - 07/04 (7)

- ► 06/20 - 06/27 (4)

- ► 06/13 - 06/20 (3)

- ► 05/30 - 06/06 (1)

- ► 05/23 - 05/30 (5)

- ► 05/16 - 05/23 (3)

- ► 05/09 - 05/16 (6)

- ► 05/02 - 05/09 (7)

- ► 04/25 - 05/02 (2)

- ► 04/18 - 04/25 (4)

- ► 04/11 - 04/18 (3)

- ► 04/04 - 04/11 (1)

- ► 03/28 - 04/04 (2)

- ► 03/14 - 03/21 (2)

- ► 02/28 - 03/07 (1)

- ► 02/21 - 02/28 (2)

- ► 02/14 - 02/21 (12)

- ► 02/07 - 02/14 (1)

- ► 01/31 - 02/07 (4)

- ► 01/17 - 01/24 (1)

-

►

2009

(98)

- ► 12/20 - 12/27 (1)

- ► 12/13 - 12/20 (2)

- ► 12/06 - 12/13 (1)

- ► 11/22 - 11/29 (3)

- ► 11/15 - 11/22 (1)

- ► 11/08 - 11/15 (1)

- ► 11/01 - 11/08 (1)

- ► 10/25 - 11/01 (7)

- ► 10/18 - 10/25 (1)

- ► 10/04 - 10/11 (1)

- ► 09/27 - 10/04 (2)

- ► 09/20 - 09/27 (1)

- ► 09/13 - 09/20 (4)

- ► 09/06 - 09/13 (3)

- ► 08/30 - 09/06 (3)

- ► 08/23 - 08/30 (1)

- ► 08/09 - 08/16 (2)

- ► 08/02 - 08/09 (1)

- ► 07/26 - 08/02 (1)

- ► 06/28 - 07/05 (6)

- ► 06/21 - 06/28 (12)

- ► 06/14 - 06/21 (43)